Robespierre on a Rampage: The Great Fear

Marat was dead, the Girondists were dead and now Danton was dead. Robespierre was swiftly killing off his opponents, but he was also making enemies with his supporters. Those who survived the Great Terror feared that any misstep might sign their own death warrants. People obeyed Robespierre lest they be sent to the guillotine next. But by mid-1794, his long-silent detractors couldn't stay quiet much longer.

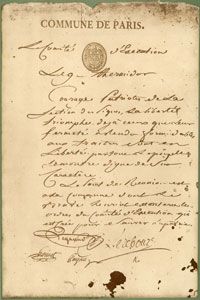

Robespierre's final ploy for wresting the counter-revolutionaries from France was the Great Fear. During this nationwide witch hunt, Robespierre was responsible for nearly 800 executions a month. As if national genocide weren't enough, Robespierre began isolating the people even further with his unexpected endorsement of a new religion.

Advertisement

The Cult of the Supreme Being was ostensibly something that Robespierre made up himself. The supreme being was, naturally, reason. Robespierre had long fantasized about a perfect republic in which people participated in government and heeded the universal guiding lights of reason and logic. But would the French people willingly worship this non-god? They'd been forcibly cut off from their Catholic roots -- Christianity had been purged from the nation in an effort to rid the people of their superstitions and faith in non-Republican entities. With the surviving French people becoming increasingly wary of their police state, they wondered: Was Robespierre power hungry or just plain mad?

Their answer seemed divinely delivered on June 6, 1794, the day Robespierre appointed as the Festival of the Supreme Being. In the center of Paris, a papier-mache replica of a mountain was constructed, and Robespierre appeared on top of it, clad in a toga. This seemed to clinch popular opinion that Robespierre was no longer a viable leader -- he'd been deluded into thinking that he was a god.

Robespierre sensed the people's change in attitude and retaliated by drafting a new list of public enemies who would be sent before the tribunal and executed. When he arrived at the Convention to deliver the list, he was seized and carried off with his allies to city hall. He was supposed to have been tried the very next day, but he couldn't bear the thought of the guillotine. Robespierre shot himself in a foiled suicide attempt. It was a poor shot -- he blew off his jaw and survived. When the Convention members came to collect him, they found Robespierre lying in agony and a few of his other allies dead. He was guillotined later that day.

But Robespierre's death didn't solve much. If anything, the latest Convention coup had only confused matters more. Floundering, the Convention deputies hastily created a new government. Under the Directory, a three-chambered system with two legislative bodies called the Council of Ancients and the Council of Five Hundred, there was a complex system of checks and balances. The Directory wanted to prove to the people that it was true to the ideals of the early people's republic (circa 1789) and not Robespierre's state of terror. In its efforts to toe the line between right and left, however, the Directory pleased no one.