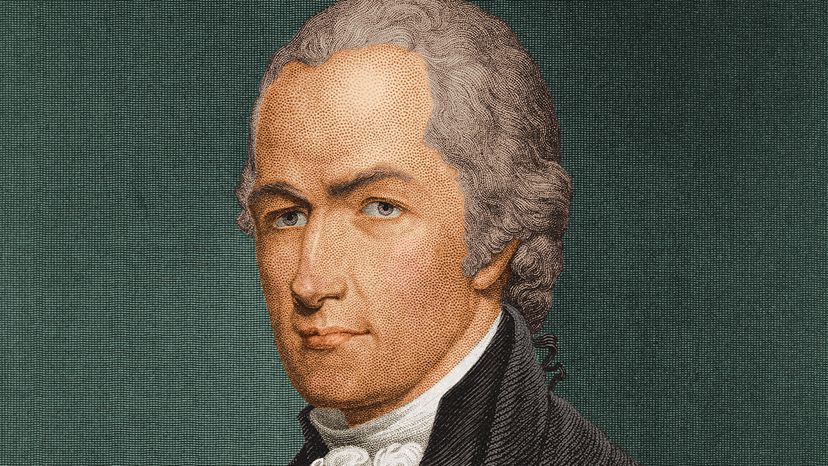

Transport yourself back to history class — your classmates, some dozing off, sit in those one-piece desks all lined up and facing the teacher. Terms like "Federalist Papers," "U.S. Mint," and "Aaron Burr" stand out in white chalk on a smudged, green blackboard. "Why do they call it a blackboard if it's green?" you wonder, your mind drifting as the teacher mentions something about a duel. Wait, a duel? Where people shoot at each other? That's interesting. She's talking about Alexander Hamilton — you know, the guy on the $10 bill.

Unless you're a history buff, that might be about all you remember about this Founding Father. But given the popularity of the hit Broadway musical Hamilton, it might be time to brush up on his biography a little bit. "My name is Alexander Hamilton," lead actor Lin-Manuel Miranda raps (yes, raps) in the opening number, "and there's a million things I haven't done. But just you wait." Luckily, you won't have to wait long to find out what he did as we have everything you need to know about the life and legacy of the "ten-dollar founding father" right here.

Advertisement

Let's start at the beginning — and quite a beginning it was. Hamilton, born in 1757 on the Caribbean island of Nevis, was the illegitimate son of James Hamilton, a poor Scottish merchant, and Rachel Faucett, an English-French planter's daughter. After moving his family to St. Croix, James abandoned his two sons and Rachel, who died in 1768. Left to fend for himself, Alexander began working for Beekman and Cruger mercantile. The business' proprietor quickly recognized the young orphan's talents and paid to send him to King's College (now Columbia University) in New York [sources: National Archives, New York Historical Society].

Hamilton enrolled at King's in 1773, and like any college student he enjoyed his share of extracurricular activities. But Hamilton's main diversion wasn't sports, partying or girls; rather, he sowed his wild oats writing political pamphlets. Still just a teenager, Hamilton made a name for himself when he penned the pro-American work "A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress," which defended a proposed trade embargo with Britain. It was no surprise, then, when the young firebrand joined the Continental Army soon after the colonies declared independence from Britain in 1776. There he met George Washington, and that's when things really got exciting for Hamilton [source: New York Historical Society].