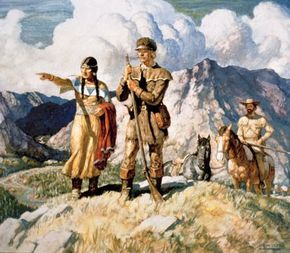

Exploration and discovery have been a part of the American experience since the land was first discovered by Europeans in the late 1400s -- we're a nation obsessed with adventure and adventurers. And no expedition of discovery has helped to shape the United States quite like the one led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who set out in 1803 to find an all-water route to the Pacific Ocean.

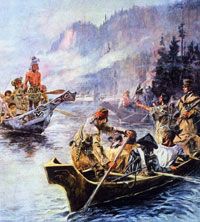

The purchase of the Louisiana Territory that year had opened vast lands for Americans to settle. Under orders from President Thomas Jefferson, Lewis, Clark and their group of woodsmen, hunters, translators and boatmen -- "The Corps of Discovery" -- blazed a trail into the wilderness and traversed the continent for three years. Lewis shipped out of Pittsburgh on Aug. 31, 1803, and on Dec. 3, 1805, the party reached the Pacific, Clark's journal proclaiming "Ocian [sic] in view! O! The joy!" [source: Ocean in View]. The party ended their journey in St. Louis on Sept. 23, 1806.

Advertisement

The Corps didn't succeed in its primary objective of finding a river route all the way across the continent, but it was certainly successful in its other missions. The team meticulously mapped its route, identified plants and animals and opened up diplomatic relations with American Indian tribes. Its discoveries helped the nation understand its new size and assess the economic potential of the new territory.

Perhaps more importantly, the expedition also helped a new nation of people define themselves as adventurers. America could now be seen as a land of constant reinvention, a notion that persists in the psyche of its citizens to this day.