The English settlers known as the Puritans and the Pilgrims have a lot in common, but only one of them arrived on the Mayflower and shared a Thanksgiving meal with the Wampanoag Indians. The other came later and waged war on the Native Americans.

From a religious standpoint, Puritans and Pilgrims are almost identical. Technically, they're both Puritans because they both wanted to "purify" or reform the Church of England, but they had different ways of going about it. The Puritans tried to reform the church from within, while the Pilgrims were known as "separatists" who believed they had to leave it.

"The Pilgrims sail to America because they want to be left alone to do their own thing; if England falls into the sea, so be it," says Sarah Crabtree, a history professor at San Francisco State University and author of "Holy Nation: The Transatlantic Quaker Ministry in an Age of Revolution." "The Puritans are intent on setting up this model utopian society and to inspire England to purity."

The Pilgrims got their name (much later) from a passage in William Bradford's "Of Plymouth Plantation" describing the group's tearful departure from the Netherlands: "So they left that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits."

The Pilgrims arrived first on the Mayflower and established the Plymouth colony in 1620. Poor and unprepared, they lost almost half of their 102 settlers to cold and famine before the Wampanoag came to their aid. The Puritans, mostly middle-class merchants, came a decade later on 17 ships and established the much larger and more prosperous Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Once in the New World, the theological distinctions between the Pilgrims and Puritans — separatists versus non-separatists — became meaningless, says Francis Bremer, professor emeritus of history at Millersville University of Pennsylvania and author of several books on the Puritans, including "Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction." For example, the Puritans in Massachusetts Bay Colony followed the Pilgrim's new method of establishing a church far from England's soil, which was for a congregation of believers to agree to a covenant or contract among themselves.

"And that's what Massachusetts does," says Bremer. "They follow the example of the Pilgrims and there's really no distinction."

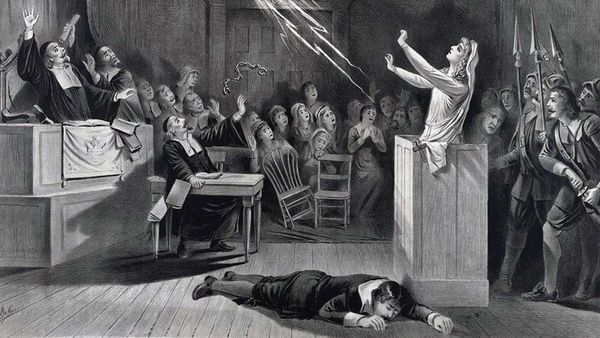

Crabtree believes that the Puritans and Pilgrims distinguished themselves in their treatment of the Native Americans they encountered.

"The Pilgrims have a working relationship with Wampanoag people when they come here, but the Puritans weren't interested in that," says Crabtree. "The Puritans show up in 1630 and by 1636 they're at war with Native Americans."