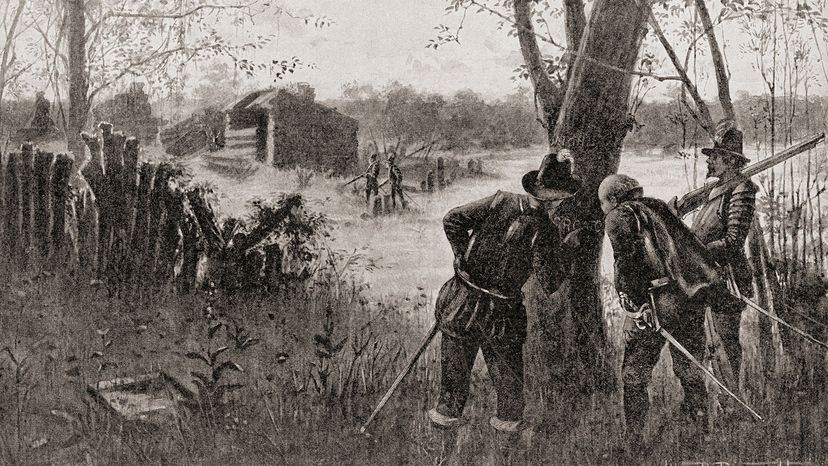

It must have been unnervingly quiet as John White made his way through the abandoned settlement at Roanoke in 1587. In the three years since he'd left, the colonists on Roanoke Island had vanished without a trace. What horrors had taken place here? Where had his family and the others gone?

What had once been a settlement of two-story, thatched-roof cottages was lost. The first seed of English presence in the New World, given purchase through the efforts of 115 people, had been uprooted inexplicably. In its place, a husk remained. The houses had all been taken down. A roughly built fort surrounding the former settlement was all that signaled the former presence of the colonists. And on a post was carved one of only two clues: the word "CROATOAN." On another tree, White found the carving "CRO."

Advertisement

That was it. The small cannons and boats that should have been situated at the nearby bay were gone. Chests with drawings, maps and books that White had buried nearby years earlier were torn apart and ruined by weather. There were no bones, no corpses – no evidence one way or another to show what had befallen the colonists, save for the evidence provided by their hastily assembled fortress. These 115 people were lost forever, never to be heard from again.

This group of settlers came to be known as the lost colony of Roanoke. The shroud of mystery surrounding their fate has kept them alive in the annals of U.S. history as much as the successful colonies that followed.

There were two expeditions to Roanoke before what would become the lost colony was established in 1587. The first was exploratory, the second (in 1585) consisted of 100 men who lived on the island for 10 months before returning to England. These early expeditions quickly deteriorated any initial warm feelings the Native Americans had toward the English. The settlers routinely kidnapped local tribal leaders and held them for ransom, despite relying on these "savages" for food and supplies [source: Lane].

When the 100 men left the 1585 Roanoke colony, it was due to constant threat of attack and waning food. Had they stayed for two more weeks, the men would've received supplies from England. A ship arrived and, finding the colony deserted, left behind 15 soldiers to maintain an English presence in the New World until another group of colonists could be brought.

This next group would become the lost colony of Roanoke. The 1587 settler population included women and children and looked much more like later successful colonies. Their arrival at Roanoke Island was an inauspicious one: They found the settlement abandoned and in shambles. The bones of one of the 15 soldiers there before them were the only physical evidence of what had befallen the previous settlers.

Led by Gov. John White (who'd been a member of the 1585 colony), these fresh colonists sought to carve out a life on the North Carolina island. They managed to turn the tide of bad relations with one nearby tribe, Powhatans living on Croatoan Island. The other tribes in the area maintained their distance. This left the colonists dependent on supplies from England, and in August 1587, Gov. White left to gather more provisions. When he returned, he found that the colony – including his daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter (Virginia Dare, the first English child born in North America) – was gone.

The carved word "CROATOAN" was an obvious clue. Perhaps the colonists had moved in search of protection or a steady food supply from the Powhatans. It appeared they hadn't left under duress; there were no Maltese crosses carved anywhere, the agreed-upon signal the colonists would use to indicate that danger had befallen them [source: Encyclopedia Virginia].

Yet no search of Croatoan Island was ever launched. Subsequent expeditions to locate the lost colony either failed or were undertaken as an excuse for piracy or other commercial endeavors. It wasn't until the Jamestown Colony was established in 1607 that any earnest searches were conducted to discover the fate of the lost Roanoke colonists.

Not only were the colonists themselves lost, the colony was as well. Poor record keeping among White and others as well as years of abandonment have kept the exact whereabouts of the 1587 colony a mystery. Numerous digs on Roanoke failed to produce any evidence of the lost colony. Remnants of the 1585 settlement have been discovered, but no evidence of the lost colony has been found. One problem is that primary sources tell different tales. From Gov. White's writings, the second settlement should be located near the first on the north end of the island. But a 1589 affidavit of a Spanish sailor puts the settlement near the center of the island where the cannons were stationed.

An old well and a small cannon found near the bay support the Spaniard's deposition. Some historians now believe that the 1587 Roanoke settlement currently lies underwater, victim to centuries of erosion.

For 400 years, Europeans have searched to uncover the truth behind the lost colony. Some interesting clues turned up early on, beginning with the Jamestown settlers.