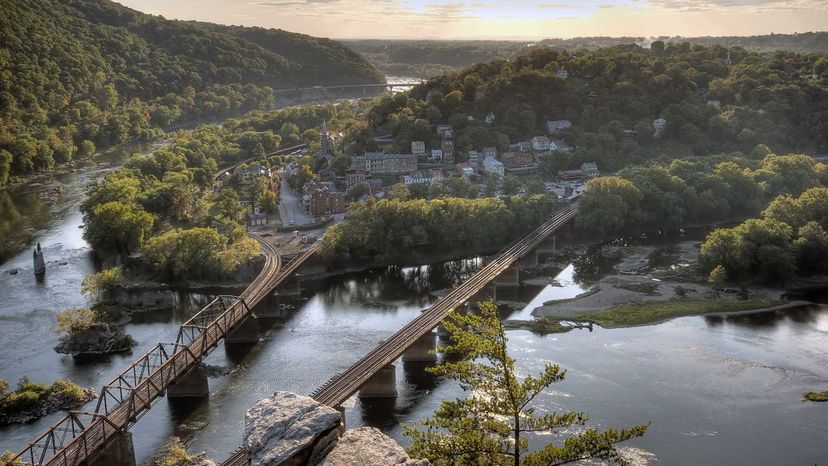

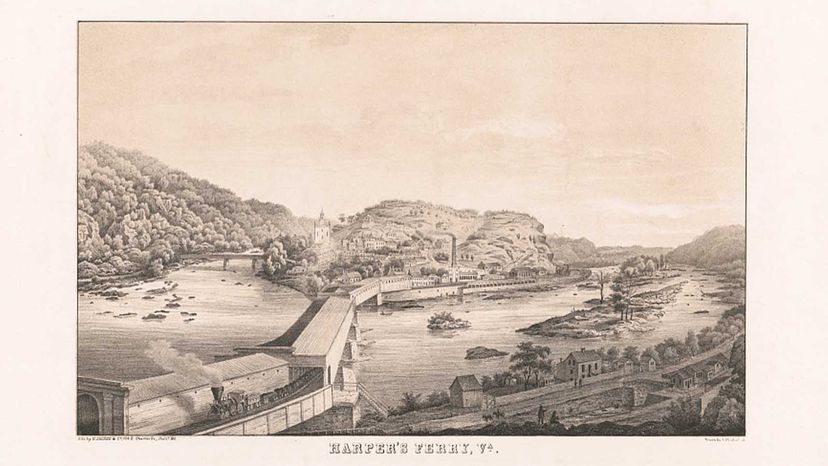

At the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, near a spot in the water where Maryland, Virginia, and the easternmost tip of West Virginia converge, lies Harpers Ferry, a quaint, sometimes bucolic 19th-century town with a rich and dizzying history.

In the early 1800s, Harpers Ferry became a pioneer in the way goods were manufactured, beginning with munitions. Just 70 miles (112 kilometers) or so northwest of Washington, D.C., it bloomed into an American transportation hub, with railroads, bridges spanning the two rivers and boats carrying goods throughout the new country.

Advertisement

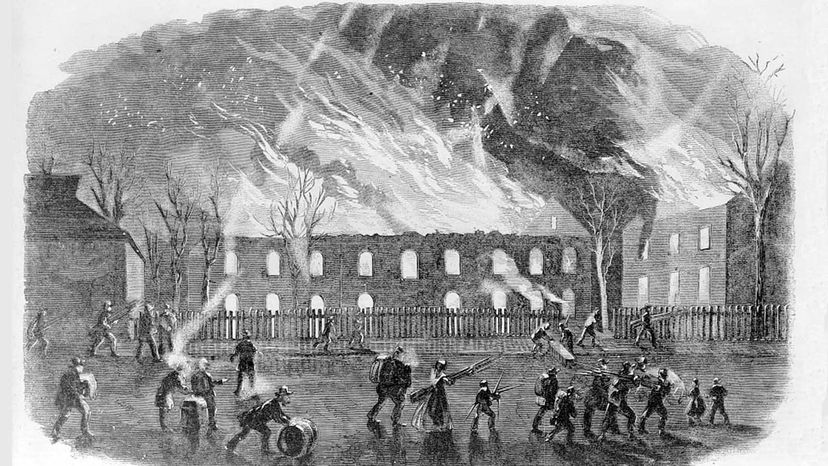

During the Civil War, it changed hands from Union to Confederate and back again at least eight times. Things got so confusing that the townspeople were called both rebels (when the Union army occupied) and Yankees (when the Confederates were in charge). A church in town flew a British flag, just to be safe.

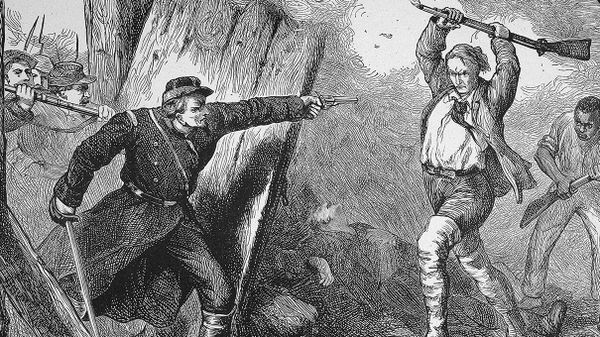

But it was in 1859, a few years before the Civil War, with a bold and disastrous bid to launch a slave rebellion, that famed abolitionist John Brown truly put Harpers Ferry on the map.

"It's a very complicated place, and it's hard to tell one story of Harpers Ferry," says Paul Shackel, an archeologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Maryland. "There's a lot of different stories and a lot of different histories."

Advertisement