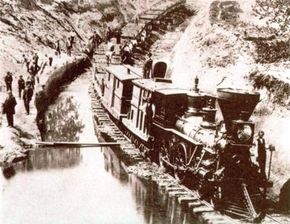

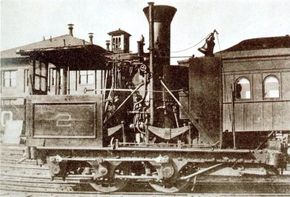

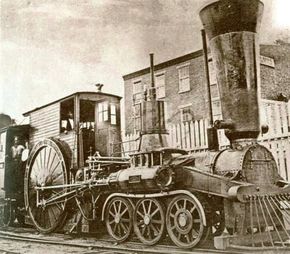

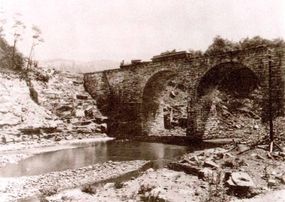

To nineteenth-century Americans, the United States seemed unimaginably vast. Yet they lacked the one thing they needed most to fulfill their destiny: reliable, all-weather transportation. Common roads, canals, and steamboats merely whetted the country's appetite for mobility. One technology in particular -- the "rail road" -- offered dependable, year-round transport anywhere a narrow path for two rails could be carved. It was the tool Americans had been waiting for, and they used it vigorously to settle the continent.

Imagine, for a moment, how Americans of the early nineteenth century must have felt gazing westward toward two million square miles of fledgling country. Promoters estimated there to be a thousand million acres available for settlement and exploitation, and practically every acre held the promise of freedom, prosperity, and the chance for a new life built on hard work and initiative.

Advertisement

Wealth, in the form of good farmland and grass for stock grazing, or metals like lead and gold, was there for the taking. Better yet, the United States tolerated no aristocrats, and there were no centuries-old traditions limiting what a man and his family could do in pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness. Yet with few exceptions, there was no effective way to reach that promised land, or to ship back the fruits of human toil.

George Washington recognized the need for some kind of transportation network. "Smooth the road and make easy the way," he wrote, "and see how amazingly our exports will be increased and how amply we shall be compensated for the expense of effecting it."

Railroads intensified a transportation revolution, the results of which were astonishing. At no other time in history has a people settled so large an area and wrested from it so much wealth in so short a time. Both the conquests of Alexander the Great and the rise of the Roman Empire pale in comparison with the expansion of the United States and Canada across the North American continent. Admittedly, that incredible growth came at great cost. Native Americans were displaced from their ancient lands, nature was continuously assaulted during the rush to build an industrialized society, and the United States suffered one Civil War and many smaller skirmishes in the struggle to define itself. Yet the undeniable result was a continent that, despite its ongoing turmoil, has enjoyed a degree of power, affluence, and accomplishment unprecedented in human history.

None of that would have been possible without effective, cheap, fast transportation. The railroad provided just that, making it possible to have truly national markets, cultures, languages, and governments. In the United States, those bonds of steel helped fulfill the national motto E Pluribus Unum, or "From Many, One."

Advertisement