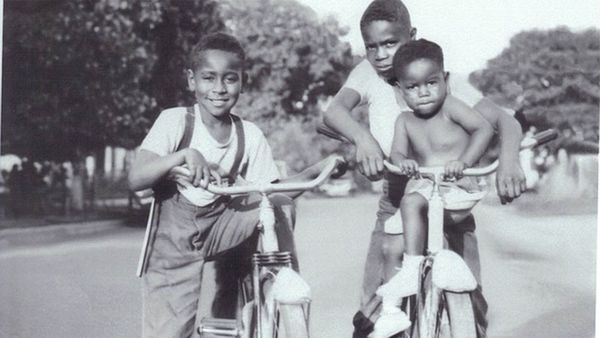

At a certain time in American history, if you happened to be of a certain racial heritage — that is to say, not white — it was probably best not to hang around after dark in certain cities and certain places. It was possibly dangerous. Sometimes deadly.

That applied to a lot of places before, roughly, the 1960s. Before racial discrimination was widely condemned, before the Civil Rights era. Before Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and the Edmund Pettus Bridge incident.

Advertisement

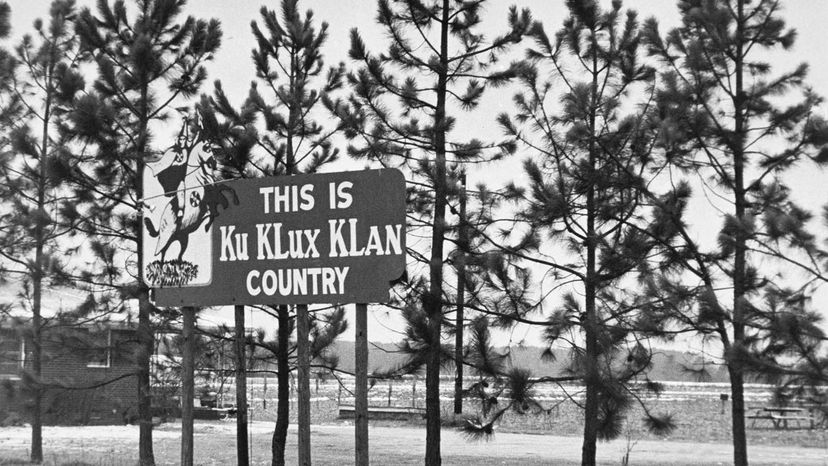

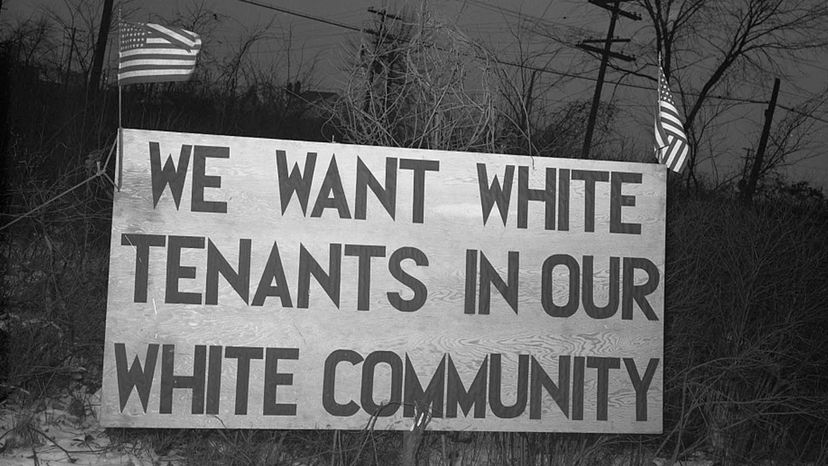

But all-white "sundown towns," as these places were known — so called because Blacks were advised to get out of town before sundown — aren't relegated to ancient history. Some are around today, still, in places all over the United States. They may not be as blatant about their racism as they once were, when signs on the edges of towns literally warned Blacks to stay away. But they're still here; small all-white Midwestern towns and huge all-white suburbs in the North, West and South.

"Our history textbooks give us a picture of the United States [where] we started out great and we have been getting better, kind of automatically, ever since," says sociologist James Loewen, who literally wrote the book on sundown towns — it's called "Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism" — back in 2004. "It isn't true. Sometimes, we've gotten worse. And race relations is one of the areas where we got worse."

Advertisement