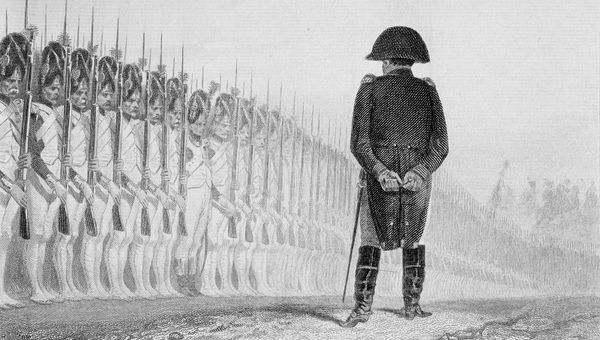

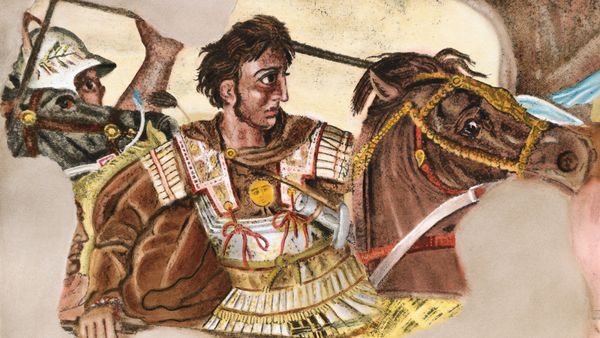

It didn't take long for Napoleon to begin seeing himself as the French incarnation of Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great. He could have made a play for emperor in 1797, but felt the moment wasn't quite right in Paris. So he rallied his armies and set off for Egypt, where he hoped to cut off British trade with India.

Napoleon scholar Jean Tulard called the Egyptian campaign, "probably the craziest expedition in the history of France." Napoleon marched 35,000 troops across the desert from the port city of Alexandria toward Cairo. At the Battle of the Pyramids, he faced a wall of 10,000 fearless Mameluke fighters on horseback.

"Soldiers," Napoleon shouted to his troops, "from the height of these pyramids, 40 centuries look down upon you."

The French, following Napoleon's ingenious battlefield strategies, crushed the saber-wielding Mamelukes and took Cairo. But while Napoleon was daydreaming of conquest — "I saw myself founding a new religion," he later wrote, "marching into Asia riding an elephant, a turban on my head, and in my hand the new Koran" — the British struck back, destroying the French fleet docked in the Mediterranean.

Stranded in Egypt, Napoleon decided to pick more fights with the locals. He took on the Turks in Syria and bombarded the centuries-old walls at the ancient city of Acre. But by 1798, morale was low and a civil war was raging back home. Napoleon saw an opening for his triumphant return, so he abandoned his troops in Egypt and secretly made for France.

The Egyptian campaign wasn't a total wash, though. Napoleon's soldiers, while digging to reinforce a fortress wall in 1799, made an accidental discovery in the Nile Delta — the Rosetta Stone.