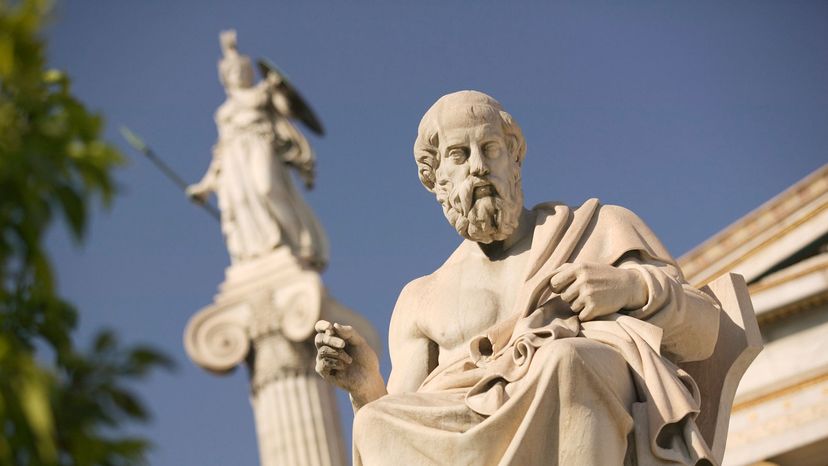

All of Western philosophy, wrote the British mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, is "a series of footnotes to Plato." The ingenious Greek philosopher, who started as a young devotee of Socrates, laid the groundwork for more than two millennia of philosophical thought. Plato's "dialogues," including "Republic," are required reading for every serious student of philosophy, and his Academy in Athens set the model for the modern university.

So, who was this man?

Advertisement

Plato of Collytus was born around 428 B.C.E. in the waning days of the Golden Age of Athens. He met Socrates as a youth and was a close follower of the provocative street philosopher, who confounded politicians and prostitutes alike with his unrelenting questions, now known as the Socratic method.

Plato was around 20 when Athens lost the disastrous Peloponnesian War to rival Sparta (he served briefly in it). After considering a career in politics, Plato grew disenchanted by corrupt leaders and the tragic execution of Socrates, his hero and mentor. Plato came to believe that only "right philosophy" could end human suffering and ensure justice.

Plato turned his energies to education, studying under Pythagorean mathematicians and traveling through Sicily, Italy and Egypt. In his early 30s, he returned to Athens and founded his academy in an open-air grove. Open to men and women, it drew the best and brightest from the Greek-speaking world — including a young Aristotle — to learn mathematics and natural philosophy.

Plato never married or had any children. He died in his early 80s but lives on in his captivating prose and thought-provoking questions, recorded in 30 lively and challenging dialogues.

Advertisement