While Roman leaders cavorted and gulped wine, impoverished commoners seethed with resentment and rage. Then, one man became a symbol of an uprising against political corruption and moral callousness, and to this very day he's regarded as a hero.

His name? Spartacus.

Advertisement

Spartacus, a Thracian man, wasn't born to wealth or power. Instead, he was considered part of the dregs of society. Born in roughly 109 B.C.E., his life's mostly a mystery to history until he became a thorn in the side of the Roman Empire.

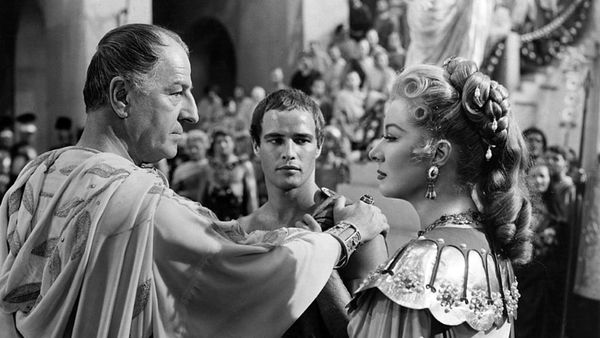

But we do know that he was sent to a gladiator school in Capua where he was trained to fight others with various weapons, as entertainment for massive crowds in arenas. Discipline in these schools was harsh.

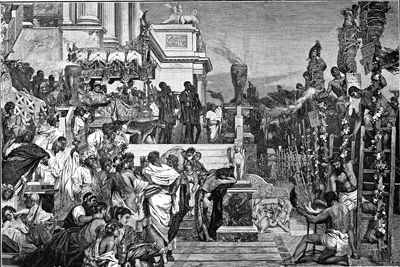

"Gladiators were a longstanding tradition in Rome, one that was originally related to funerals. Fundamentally though, gladiators were slaves, and generally they were considered the lowest of the low, the most worthless and useless of slaves," says Aaron Irvin, a history professor at Murray State University in Kentucky. Irvin is a well-regarded historian who's also consulted on many TV series, including "Spartacus" (2010), "Spartacus: Gods of the Arena" (2011), and "Roman Empire" (2016).

"A slave was made a gladiator as a last resort, because the owner saw no other feasible way of making money off of the slave, so he might as well make the slave's death entertaining," he says in an email interview.

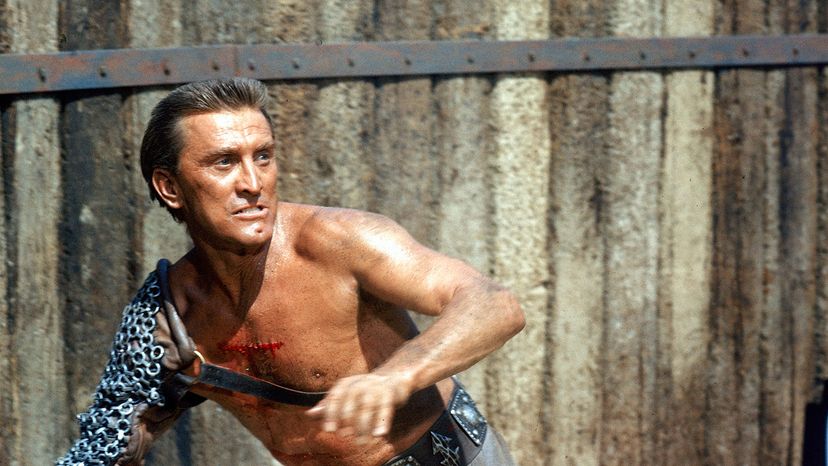

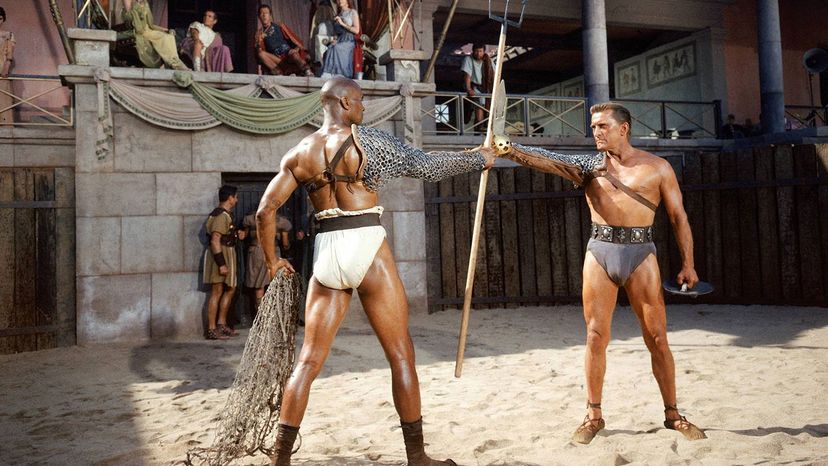

Not all gladiator fights were to the death, notes Irvin. Some ended when a fighter drew first blood or drove his opponent into submission. But in an age where basic hygiene like handwashing was rare and antibiotics didn't exist, even superficial wounds could prove fatal for one or both fighters. And many fights only ended when one gladiator had killed another.

A few fortunate gladiators found fame through bloodshed. They won fight after fight, making names for themselves and becoming something akin to Roman rock stars. They had slaves to look after them and in very rare cases became the most popular figures in their cities.

"Gladiator helmets were crafted to specifically hide the face of the gladiators, making the fighters recognizable in their gear, but otherwise faceless automata to the crowd," says Irvin. "No longer debased slaves, the gladiators became something extraordinary, something beyond mere humans."

Advertisement