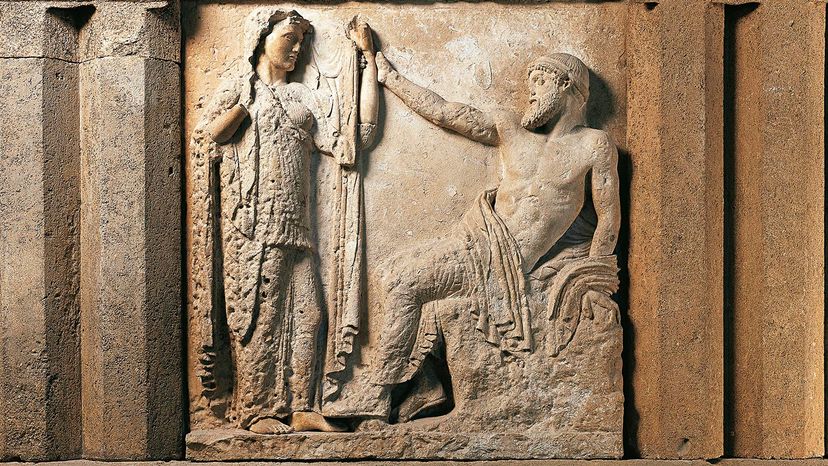

Behind every Greek god, there is a Greek goddess (or seven, if you're counting all of Zeus' wives). But Hera stands out among the crowd as the Queen of the Gods, and despite her husband/brother's (remember, this is Greek mythology) reputation for getting around, she holds the crown as the supreme goddess of marriage, women, the sky and the stars, and she's usually the one depicted by Zeus' side rocking a wreath and veil.

"As the wife (and sister) of Zeus, she is a powerful queen whose strong feelings and opinions often are opposed to her husband's," says Richard P. Martin, Antony and Isabelle Raubitschek professor in classics at Stanford University. "Proud, jealous and quick to take action when she feels spurned, she can be a danger to gods and mortals who get in her way."

Advertisement

But according to Martin, Hera also has a softer side. "On the other hand, she is fiercely protective of the institution of marriage, and also the one who watched over women in childbirth," he says. "In some places, she was even identified with the goddess of childbirth, Eileithyia."

Born to Kronus and Rhea, Hera gained a reputation as the only "really married goddess among the Olympians," and she had three children with Zeus: Ares, the god of war, Heba, the goddess of youth and Hephaestus, the god of metallurgy. She also gave birth to one son all on her own (again — that's Greek mythology for you). Learn more about that particular story and more in the following three Hera facts:

Advertisement