In some ways, the medieval Nizari Ismaili strategy actually seems like a less brutal way to wage war than their adversaries with conventional armies, who often wreaked destruction upon civilians as well as the enemy. As modern Ismaili scholars have emphasized, the medieval faction acted in self-defense, and attacked only political and military figures, but not the larger population. And as Waterson notes, they turned to targeted killings largely out of necessity — not to seize power, but to survive.

"The Nizari Ismailis were essentially a very conservative faction, and very limited in terms of their appeals for mass conversion, and essentially wanted to continue their way of life and their way of faith without persecution," Waterson, an alumnus of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and a former teacher, explains in a lengthy email.

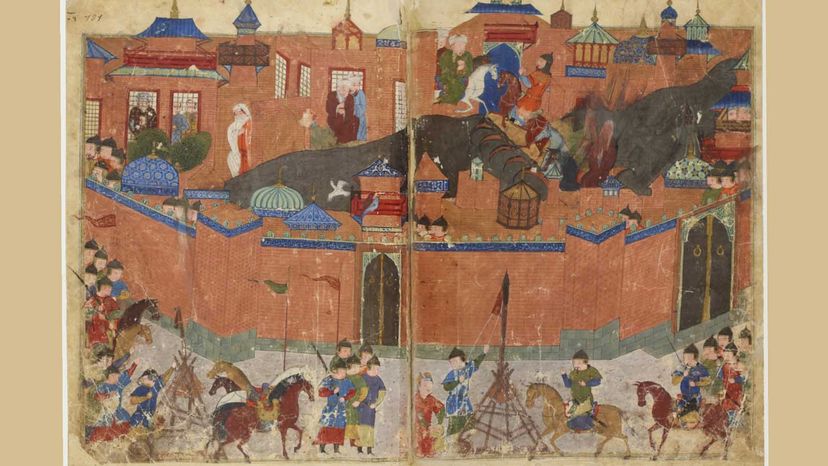

Though the Nizari Ismailis had fortified strongholds, they lacked the military might and numbers to withstand sieges by enemy armies. Waterson describes Hassan Sabah, their founder, as a highly educated man with experience in government, who wisely made the calculation that the best way to relieve the pressure from a superior besieging force was to decapitate it.

"Hitting at the top of the pyramid when you have limited resources shows a clear understanding of the military society he was facing," Waterson says.

A lot of fantastical myths about the Nizari Ismailis' fighters — some of them concocted by enemies who sought to demonize them — still are floating around. Their adversaries, at a loss to explain their effectiveness, portrayed them as fanatics driven by visions of paradise induced by smoking hashish. (The term assassin comes from a medieval Latin word, assassinus, derived from the Arabic term for hashish user, according to Merriam-Webster.)

Venetian merchant, adventurer and memoirist Marco Polo, who came along after the group's defeat by the Mongols, bought into those myths, depicting them as young males "from the age of twelve to twenty years, selected from the inhabitants of the surrounding mountains, who showed a disposition for martial exercises, and appeared to possess the quality of daring courage."

And while it's tempting for the modern mind, conditioned by comic books, movie blockbusters and video games, to imagine them as a secretive force of martial arts experts fluent in multiple languages, trained from boyhood to possess extraordinary fighting skill and mastery of the arts of deception, the reality was less exotic. Historians depict the Assassins as ordinary people who were willing to risk their lives — and often to be sacrificed — out of religious piety and to protect their community.

"In this age pretty much every male carried sidearms, and farmers as we know from the chronicles, were just as capable of inflicting damage on military forces as regular soldiers," Waterson says.

And though one of the dagger-wielding assassins' classic tactics was to infiltrate enemy leaders' defenses by posing as lowly servants, harmless civilians or religious clerics, they didn't need to be masters of disguise.

"What I feel is more likely is that the internal religious fervor of the assassins allowed them to be sleepers for very long periods of time within the entourage and close personal guards of the possible candidates for assassination," Waterson says. "The assassin within your guard could then simply be 'turned on' by messaging from the grandmaster of either Syria or Persia. We see this in a number of anecdotes related to the Sultan Saladin, who at one point felt so little trust in his close personal guard that he took to sleeping in a high wooden mobile tower."