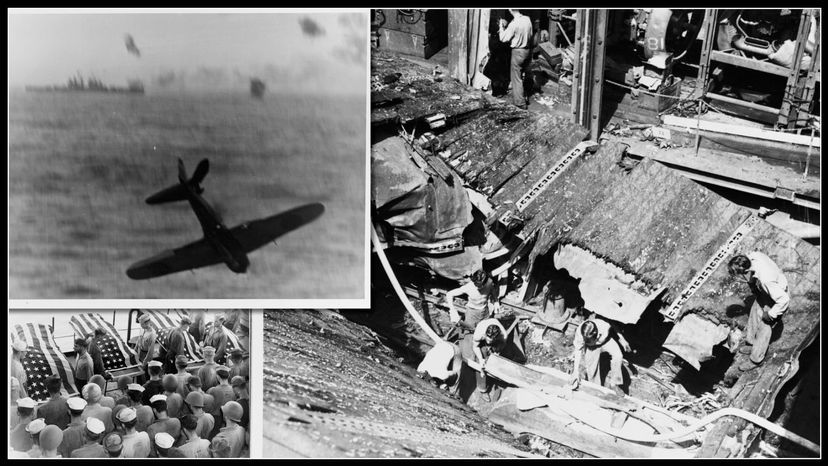

Still, when historians look upon kamikazes, it is the dive-bombing suicide planes, part of a Special Attack Corps (Tokubetsu Kōgekitai), that remain the focus.

In 1975, in Chiran, Kagoshima Prefecture in the southern part of Japan, the Chiran Peace Museum — otherwise known as the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots — opened. Thousands of articles left behind by kamikazes, including letters to loved ones before their final missions, are featured.

Here's a typical one from Corp. Takao Adachi, who took off on his final mission on June 1, 1945. He was 17. (As translated by Kamikaze Images' Gordon.)

Dear Grandmother and Father,

Decisive battle has come for me. Excitement also with instant enemy sinking.

Living as a man in this divine country that faces an extreme emergency, in my heart I am absolutely satisfied that I have a good place to die as a member of the Special Attack Corps Makoto Hikōtai (Flying Unit).

I warmly thank each of the officers, instructors, and senior comrades when I was a flight cadet.

In response to your great kindness in raising me for more than 18 years as a son in this divine land, I have not been able to do anything to repay your kindness. I imagine that my going before you must be painful above anything else.

Furthermore, I am determined that I certainly will carry out a certain-death, sure-kill (hisshi hissatsu) body-crashing (taiatari) attack and instantly sink an enemy ship.

Grandmother and Father, please be glad with the daybreak when I splendidly sink at once an enemy ship.

Finally, I will make a body-crashing attack while praying for still more prosperity of this divine country Japan.

On the eve of sortie, Takao

"The big topics, they're talking about filial piety to their parents, what commitment they had, and saying how sorry they were that they were leaving and dying, basically," Gordon says.

The letters have helped portray the young men who flew these missions — their average age was around 21 — not as crazed suicide bombers but as loyal sons of Japan, heroic and worthy of praise. It's a widely held belief in Japan, though not everyone thinks that way.

In comparison, many Americans — especially older ones — see kamikazes only as those grim Zero pilots bearing down on poor American soldiers, bent on killing and destruction. Instead of heroism, they see madness.

That may have changed some over the generations. "In the U.S., it's probably not as extreme anymore," Gordon says. "But I will tell you, people were emotional when I talked to them about it on the U.S. side [when he did research back in the early 2000s]. Some people didn't even want to talk to me."

Kamikazes, in the end, were fighters on the front line of a war that their side was losing badly. Americans already were bombing cities in Japan from bases in China. More raids were coming. The kamikazes were Japan's last resort. And so they went out fighting for their country.

"I still think," Gordon says, "that most of them believed that there was a good chance that they could somehow at least stop the American advances — if not necessarily win the war — and not have the destruction of Japan."