In all of history, no cow is more infamous than Mrs. O'Leary's. The farm animal was accused of kicking over a lantern and starting the Great Chicago Fire on Oct. 8, 1871. The fire, despite its humble origins in a barn, was ferocious. It destroyed 3.5 square miles of the city and left 120 people dead and thousands more homeless. Losses were estimated at $200 million [source: Gove].

Mrs. O'Leary lived with her husband and five children at 137 DeKoven Street in Chicago. The O'Learys were a poor family; Mr. O'Leary worked as a laborer, and Mrs. O'Leary kept her infamous cows in a backyard barn and sold their milk to the neighbors.

Advertisement

After the fire, newspapers immediately pointed fingers at Mrs. O'Leary. The Chicago Tribune claimed that Mrs. O'Leary had a motive for starting the fire. She'd been on welfare, but when the city learned that she sold milk on the side, it cut her off. In response, the peeved Mrs. O'Leary swore her vengeance on the city, the paper claimed. And now she'd had her retribution.

Other newspapers were a bit more gracious. They reported that the fire was an accident -- that a kerosene lamp was knocked over during milking, either by the cow or by Mrs. O'Leary.

Mrs. O'Leary maintained, however, that her entire family was asleep in the house when the fire started. The official inquiry into the fire -- despite its over one thousand pages of testimony -- did not determine the exact cause of the fire. But the damage to Mrs. O'Leary was done, and she and her cow have lived on in Chicago legend.

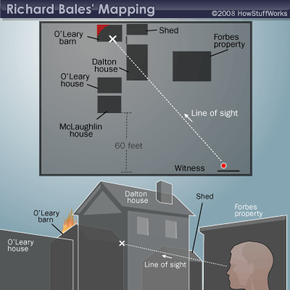

Historians generally agree that the fire started in the barn behind the O'Leary home. But did the cow really kick over a lantern? Was someone besides Mrs. O'Leary to blame? Several other characters lurk on the edges of this crime scene. Let's take a look at these possible culprits on the next page.

Advertisement