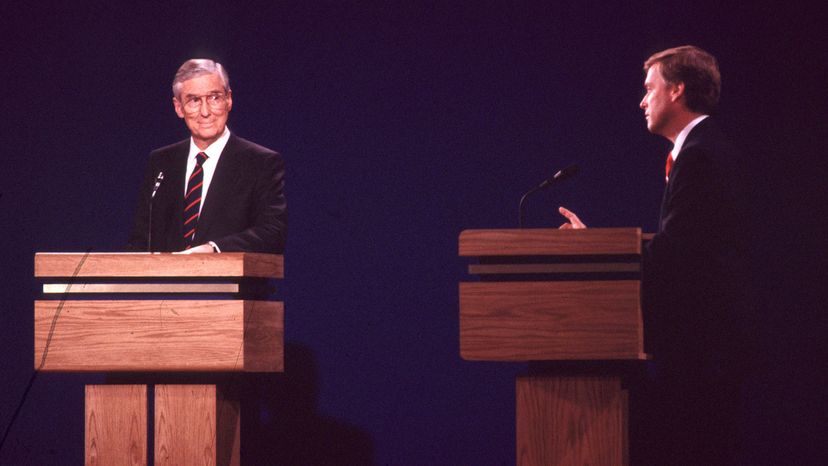

For the first time in history, the two party-nominated candidates for president of the United States were about to debate with television cameras trained on them. And President Richard Nixon was beginning to regret agreeing to it.

In the studios of a CBS affiliate in Chicago on Sept. 26, 1960, he felt like death warmed over. The month earlier, he'd slammed his knee into a car door, an injury that developed into a staph infection. He'd just spent two weeks in the hospital, and now, with the cameras about to roll, he was sweating, 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) underweight and feeling terrible. Some guy had painted the backdrop almost the precise shade of gray as Nixon's suit, and he was fading into it. As if things couldn't possibly get worse, his opponent, Sen. John F. Kennedy, had spent the past month taking it easy on the campaign trail in sunny California. He looked tan, rested and as fit as Nixon had ever seen him.

Advertisement

That first debate was a groundbreaking event. More than 66 million people watched it on television [source: The Commission on Presidential Debates]. Historians would capitalize the "d" in debate and place the word "Great" in front of it. And Nixon looked seriously ill throughout.

Before the first debate, Nixon had been in the lead. The next day, polls showed Kennedy slightly ahead. Later polls found more than half of voters said the televised series of four debates had shaped how they cast their ballots (Nixon was judged to have won two of the later debates by voters). Six percent said they voted specifically according to their impression of the debates [source: History]. In November, Kennedy won the presidential election.

No longer was politics only about the issues and whatever a campaign could plant in the papers; they were also about aesthetics now. No longer were debates for the benefit of the few people in a room. They were now about the tens of millions who tuned in not only to listen to the candidates but also to watch them as well.

It's often said that radio listeners thought Nixon had one that first debate while TV viewers gave Kennedy the edge. But in reality, this wasn't true. A survey was taken of 2,100 people, and only 282 of them listened to the debate on the radio. The vast majority watched it on TV and there is no evidence to support the fact that the medium influenced a person's opinion of who won the debate [source: Morelli].

Another question was whether Kennedy's performance on that first debate won him the election. Some say it did, others say it didn't [source: Morelli]. But since Kennedy's win over Nixon was very narrow, it's safe to assume that Kennedy's good performance must have swung a few folks over to his side and helped him to victory.

Nixon refused to debate in subsequent presidential runs, but later candidates have all taken a turn at the podium and the presidential debate has become part of the decision-making process of Election Day in the U.S.

So how did the presidential debates get started and how do they work?

Advertisement