Phineas Taylor (P.T.) Barnum was born on July 5, 1810. Most of us know him because of the circus, but he was actually an incredibly important figure in American history. "The Atlantic" named P.T. Barnum to its list of 100 most influential figures in American history. The list includes George Washington (#2), Ben Franklin (#23) and Sam Walton (#72, creator of Wal-Mart). Barnum comes in at #67. Obviously there was more to the man than a traveling circus.

So what did P. T. Barnum do? One way to find out is to read his autobiography, which is available online for free. It is an astonishing book, and here we learn some of the things that made P.T. Barnum so great. First, he had unbelievable perseverance. He also had a keen understanding of what would excite people's interest. But his greatest talent, perhaps, was his ability to package and promote entertainment.

Advertisement

Barnum's first business opened in May 1828. He ran a small store that initially sold cakes, cookies, raisins and ale. We might think of it as a version of today's convenience store. Later, he added "stuff" that he purchased in New York -- pocket knives, combs, et cetera -- as well as stewed oysters and lottery tickets. Not long afterwards, Barnum met a man named Hack Bailey, who began to frequent the store. Barnum describes him as "...a showman. He imported the first elephant that was ever brought to this country and made a fortune by exhibiting it. He was afterwards extensively engaged in traveling menageries, and subsequently was very successful running opposition steamboats upon the North River." In other words, at age 18, Barnum was exposed to a person who had made a great deal of money doing something that Barnum would eventually turn into a fine art form.

At this point, Barnum had several unsuccessful business ventures. He opened a country store, but it failed. He tried selling books, but much of his stock was stolen. He bought a press and started a weekly newspaper, but was sued for libel several times and spent time in jail. He sold lottery tickets on credit and was unable to collect.

So in 1835, Barnum moved his family to New York City to start over again. As Barnum puts it in his autobiography, "I had learned that I could make money rapidly and in large sums, whenever I set about it with a will." But he arrived in New York essentially penniless. It is from this position that P.T. Barnum began his career as a showman.

Barnum's career started with a woman named Joice Heth, an extremely old African-American woman described as the 161-year-old former slave of George Washington's father. An ad goes on the say:

Of course Joice Heth was not actually 161 years old, but she looked it. She was nearly paralyzed (having only the use of one arm), completely blind and toothless. However she could speak, sing and hold conversations with people, and she knew a great deal about Washington and his family. Since Heth was a slave, Barnum was able to purchase her for $1,000 in borrowed money. The he displayed her in New York City. From this endeavor, Barnum made about $1,500 per week. He was able to do this because of an amazing amount of advertising -- brochures, posters, booklets, newspaper ads, et cetera -- declaring her to be "the nurse of George Washington." As interest waned in New York, Barnum took her on the road to cities like Providence and Boston.

While exhibiting Heth in Albany, Barnum met a plate-spinning acrobat named Signor Antonio, and offered to pay him $20 per week to do shows. Barnum changed his name to the more exotic-sounding "Signor Vivalla," promoted him extensively, and was soon making $50 a night for his performances in theaters.

Barnum learned about the power of advertising and the value of traveling shows from these experiences. For example, in April 1836, while arranging performances for Antonio, Barnum had his first encounter with a traveling circus, complete with tents and animals.

Barnum's next endeavor was a museum in New York. According to Ringling.com:

This museum, renamed Barnum's American Museum, was successful for many years. Barnum added several now-legendary attractions over the next few years, including General Tom Thumb (a little person whose real name was Charles Stratton) and the "Fejee Mermaid" (which was actually the top half of a monkey body sewn to the body of a fish).

In 1850, Barnum brought the celebrated opera singer Jenny Lind, known as the "Swedish Nightingale," to the United States. Although she was popular in Europe, Lind was virtually unknown in the U.S., and Barnum had never actually heard her sing. But he had no doubt that she would be successful, and he was right -- Lind was well-received and performed 95 concerts with Barnum as her manager.

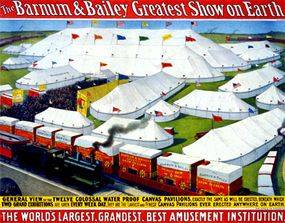

It was not until 1871 that Barnum started his circus, calling it "P.T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan and Circus." In 1872 he gave it the name "The Greatest Show on Earth." In 1881 Barnum hooked up with James Bailey, creating what eventually became "Barnum and Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth."

P.T. Barnum died in 1891, having read his own obituary. Ringling.com tells the story this way:

Several weeks before he died in his sleep, on April 7, 1891, Barnum read his own obituary: The New York Sun newspaper, responding to Barnum's comment that the press says nice things about people after they die, ran his obituary on the front page with the headline, "Great And Only Barnum -- He Wanted To Read His Obituary -- Here It Is."

What a way to go.

For lots more information on P.T. Barnum and related topics, check out these links:

Sources

- Barnum, Phineas Taylor. "The Autobiography of P.T. Barnum: Clerk, Merchant, Editor and Showman." Ward & Lock, 1865. Digitized March 29, 2006, University of Michigan. http://books.google.com/books?id=yyqNhXDSNXkC

- Ringling.com: P.T. Barnum http://www.ringling.com/explore/history/ptbarnum_1.aspx

- Saxon, Arthur Hartley. "P.T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man." 1989, Columbia University Press.

Advertisement