On May 7, 1919, in a room in the grand Versailles Palace outside Paris, German foreign minister Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau arrived at the head of a delegation of diplomats. They came to negotiate with representatives of the major Allied powers -- Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States -- following the armistice that had ended World War I in Europe. Instead of finding seats laid out for his delegation, Brockdorff-Rantzau and his colleagues, dressed stiffly in frock coats and wing collars, were made to stand like so many errant schoolboys. This was the first of many humiliations imposed on the Germans after World War I.

The Allied powers thought they had won the war and that Germany had been the architect of its outbreak. The German view that an armistice was really a truce, rather than surrender, was ignored.

Advertisement

The origins of this humiliation lay five years before, in the crisis that led to the outbreak of what became known as the Great War. The victorious Allies blamed Germany and Austria-Hungary for causing that war, but the explanation is more complex. Before 1914 Europe had entered a new phase in its history with the emergence of a group of powerful, industrialized, and heavily armed states, each of which had imperial interests to defend. National competition became the key characteristic of the age.

Earlier, in the 19th century, these states had collaborated to keep the peace, because the kings and aristocrats who dominated the political scene had a strong interest in avoiding conflict. But by the turn of the 20th century, the old regimes were in retreat and modern political movements -- many of them strongly nationalist in outlook -- had begun to emerge. The new working classes, thrown up by rapid industrialization, offered a different kind of threat, though many of them could be won over to a patriotic cause. Throughout Eastern and Southern Europe, where there existed a mixture of nationalities under imperial Prussian or Austrian or Russian rule, mass politics led to agitation for national self-determination. This issue was at its most acute in the Habsburg Empire, whose capital was in Vienna. Its rulers maintained a precarious hold on a territory that comprised a dozen nationalities, many of them eager for autonomy.

It is no accident that it was there, in the national patchwork of the Habsburg Empire, that the immediate origins of the war of 1914-18 are found. The empire seethed with conflicts -- between rival nationalities, between different classes, and between the new democratic parties and the authoritarian monarchy that ran the system. Most acute of all was the crisis with the southern Slav populations of the monarchy. Backed by the independent state of Serbia, Slav nationalists in the empire looked for a southern Slav state (Yugoslavia). In Vienna, fears arose that the Serbs would provoke the breakup of the old order.

On June 28, 1914, on an official visit to Sarajevo (capital of the recently annexed province of Bosnia), the heir to the Habsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, together with his wife Sophie, were assassinated by a young Bosnian terrorist named Gavrilo Princip. The Austrian authorities demanded action. They blamed Serbia for encouraging the Black Hand society to which Princip belonged, and demanded that Serbia accept Austrian interference in their internal investigation of the murder. The Serbs accepted parts of Austria's ultimatum but balked at other portions. This was the trigger for Austria's declaration of war.

None of the other European powers had expected or planned for war in 1914, but it was a fear that each of them had harbored. In the 10 years before 1914, many such crises had arisen. Each power's fear of the other powers fueled an arms race that produced large armies and navies with little to do but plan ways of outmaneuvering perceived enemies. Armaments did not cause war, as many believed at the time, but they contributed to a growing sense of instability and antagonism, and lessened the capacity of states to restrain the military when crisis beckoned.

This is what happened in 1914. Austria was prepared to go to war with Serbia without the other powers intervening, but it needed the support of Germany, its ally, and the neutralization of any threat from Russia. Austria got full support from Berlin, but Russia -- fearful that Austria would use the crisis to dominate the Slavic Balkans and stall Russian imperial ambitions in the region -- backed up Serbia and began to mobilize.

This decision produced a domino effect. In Berlin, it was assumed that Russian mobilization was the result of French and British encouragement. The German military persuaded the German emperor to let them carry out the so-called Schlieffen Plan, to attack France first and then to turn and defeat Russia. When Austria finally invaded Serbia, Germany prepared to attack France. Britain sided with France when the Germans invaded Belgium, which was in violation of the agreement to respect its neutrality. By August 4, 1914, all the major powers of Europe were at war.

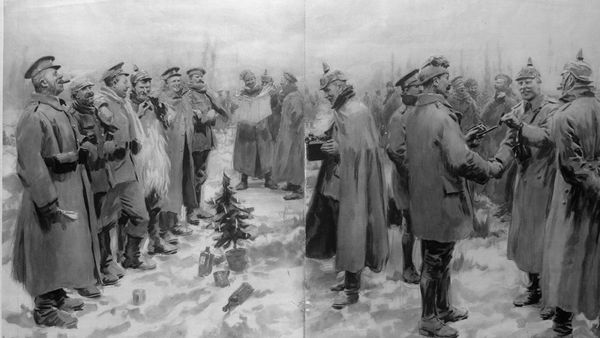

The remarkable fact is that few of the powers that entered the war really understood what form it would take. The prevailing thought was that the conflict might be resolved by a few large set-piece battles and be "over by Christmas." The war that developed could not have been more different. A stalemate developed on the Western Front, while there was much movement back and forth on the Eastern Front. Combat was dominated by artillery and the newly developed machine gun. Warfare stagnated into a terrible contest of attrition in which both sides sustained losses on scales unimaginable before 1914.

The conflict was presented as a life-and-death struggle for national survival. The Turkish Empire joined the conflict in 1914, siding with Germany and Austria. Italy entered in 1915, siding with the Western Allies. In 1917 the United States, entirely distant from the conflict when it broke out, moved to belligerency in response to Germany's unrestricted use of submarines against American shipping. In three years, the war between Austria and Serbia had become global.

To win the war, the major combatants found themselves facing an unprecedented task. It became necessary for the states to control their economies, to regiment agriculture, to direct trade, and to conscript labor (and to draw in an army of female workers). Production was directed more and more to armaments. The inflated demands of this new form of national conflict came to be known as "total war," a term coined by German general Erich von Ludendorff in 1919 to describe the mobilization of the entire economic, social, and moral energies of the nation. In the end, the economic resources of the Allied powers proved greater than those of Germany and its allies. Tanks and aircraft began to change the nature of war, and the Allies had more of both. With its allies having already been defeated and its own army beaten, Germany sought an armistice, which was signed on November 11, 1918.

In the next section, learn how Europe was reshaped after the events of World War I.

To follow more major events of World War II, see:

Advertisement