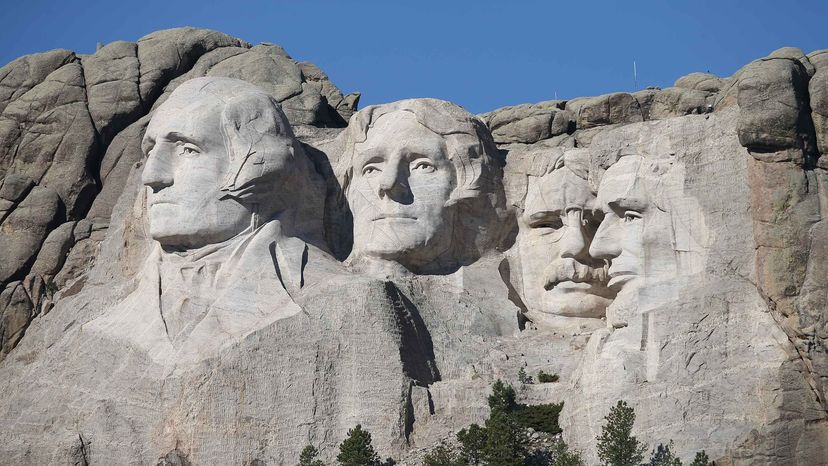

If you saw the 2007 movie thriller "National Treasure: Book of Secrets," you probably remember the part about South Dakota's Mount Rushmore containing a secret passageway that leads to a long-buried city of gold, which President Calvin Coolidge tried to conceal by having sculptor Gutzon Borglum carve 60-foot (18.3-meter) faces of four U.S. presidents, into its granite.

Okay, before you get too excited, that was just a movie. There's no gold under Mount Rushmore. But there is a 70-foot (21.4-meter) passageway carved inside the mountain, and while it's not quite top secret, the space — which isn't open to the public — does have a strange story.

Advertisement

The tunnel was created in the late 1930s by Borglum, as part of what he envisioned as one of the most important features of the monument — an 8,000-square-foot (743-square-meter) man-made cave that would contain bronze and glass cabinets filled with replicas of the U.S. Constitution and other significant documents and artifacts from U.S. history stamped on aluminum sheets, along with busts of famous Americans and exhibits extolling U.S. scientific, industrial and artistic achievements.