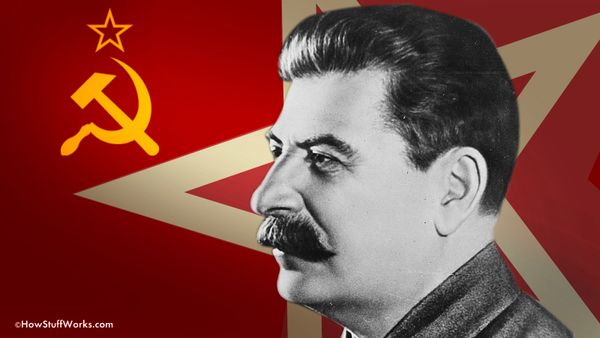

In the wake of World War II, Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha began remaking his war-torn country in the image of Stalin's Soviet Union. That is, he ruled with terrifying menace, stoking isolationism and Cold War paranoia.

Then, in the 1970s, with an ominous national mood firmly in place, he began building the bunkers. Bunkers large and bunkers small, bunkers underground and bunkers scattered openly through the countryside. Bunkers obvious, and bunkers secret.

Advertisement

The stated idea was that these reinforced concrete bunkers (bunkeret in Albanian) would serve as defensive positions during an enemy invasion that never came. Ordinary civilians were trained to rush to the bunkers in case of emergency and conditioned by propaganda to be ever vigilant against any and all foreign enemies.

It was part of Hoxha's "people's war" strategy, which relied on guerilla war tactics executed by non-soldiers. He wanted his citizens gjithmone gati, or "always ready," and most were required to do at least a little military training each year. Ultimately, though, what was really happening was that they were being conditioned to obey the hardline regime.

Because of the perpetual secrecy surrounding Hoxha's administration, the bunkers were planned and built with few public details. Engineers were moved from one work site to another, to make it impossible for anyone to fully understand the scope of the project. As such, records are scarce and no one knows how many were constructed; numbers range from roughly 175,000 to nearly 750,000.

Factory employees worked around the clock to make the necessary materials. Some bunker designs were light enough to be carried piecemeal into the mountains by mules and men. Others were dropped into place by helicopter. Still others were virtual cities, meant to survive nuclear strikes.

The project was so massive that it may have required three times as much concrete as France's equally incredible Maginot Line, which tried (and failed) to thwart Nazi hordes. Some experts estimate Albania's bunkers cost twice as much as the Maginot, too. Notably, the bunker strategy didn't sit well with officials in the standing army, in part because the clunky and often cramped bunkers weren't actually useful for professional soldiers. But that, of course, was beside the point.

"The bunkers were also about showing off the regime's military, technical and strategic ability – at a time when Albania was increasingly alone geopolitically – and in that sense they did serve a function," says Elidor Mehilli, a Hunter College associate professor of history, via email. "They were concrete things, but they also carried a kind of symbolic value. The official party propaganda spoke of Albania as 'a fortress.' The regime meant that metaphorically, in the sense of defending Communism."

Indeed, Hoxha had cut off relations with neighboring Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union and even China, feeling these countries had either strayed from the hardline Socialist path, or else were warming relations with Western countries. Having no allies made Albania one of the most isolated countries on Earth. The bunkers were allegedly to keep the country safe from its many enemies.

"Their building was above all for public consumption and not for any military purpose," adds Artan Hoxha, a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh, by email (he's no relation to the dictator). "The regime was aware that the bunkers would not help in contemporary warfare."

Advertisement