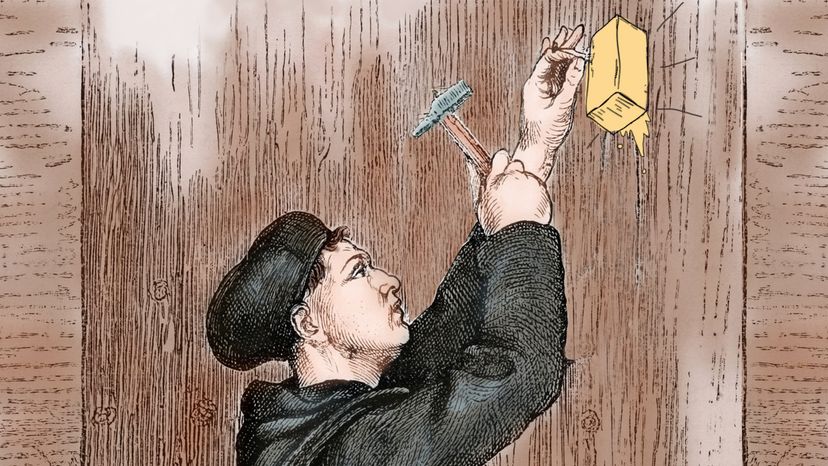

2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. And as part of the 500th-anniversary celebrations, we need to talk about butter. Yes, the tasty stuff you spread on toast and tuck into a baked potato. In an odd twist of history, butter may have played an outsized role in stoking an outspoken German monk named Martin Luther's frustration with the Roman Catholic Church. In fact, if not for a butter ban, Protestantism might have had a much slower growth.

The story begins in Medieval Europe, where "fast days" were a big deal. According to "Butter: a Rich History" by Elaine Khosrova, the tradition started with monks abstaining from eating any animal products on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and all during Lent, the 40-day period leading up to Easter. Meat and dairy was believed to fuel lust, writes Khosrova. Eventually the Church extended the fast day rules to all Christians — no meat, milk, eggs, animal fats or butter.

Advertisement

The problem was that the Roman Catholic Church was centered in, you guessed it, Rome. And people in Southern Europe didn't eat a lot of butter back in the 15th and 16th century. Their diet was dominated by fish and olive oil, both of which were totally acceptable on fast days. According to "A History of Food" by Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, some Southern Europeans believed that butter caused leprosy and packed their own supply of oil if traveling abroad.

Up north in dairy-farming countries like France and Germany — where Luther lived — cutting butter from the diet was a much bigger deal. After losing meat and cheese, there was pretty much nothing left. And since fast days covered almost half the calendar year, the butter ban was akin to starvation.

Advertisement