Chinese restaurants have become such an institution in the United States that more than 41,000 now exist in the country — about three times as many as the number of McDonald's hamburger joints. One familiar Chinese-American restaurant staple, General Tso's chicken, ranked fourth in GrubHub's list of the nation's most popular take-out foods.

But in the early-to-mid 1900s, the white establishment — local governments, labor unions and newspapers, among other institutions — in the United States supported restrictive Jim Crow laws, xenophobia regulations and racist ideology, waging a targeted campaign intending to drive the restaurants out of business. As detailed in a forthcoming article to be published in the Duke Law Journal, and first presented at the Association for Asian American Studies 2014 annual meeting, opponents of Chinese restaurants fueled their campaigns with a two-pronged argument.

Advertisement

Economically, Chinese restaurants were seen as competing with traditionally "American" restaurants, and those who worked to shut them down claimed their presence threatened the livelihoods of white restaurant owners, cooks and waiters.

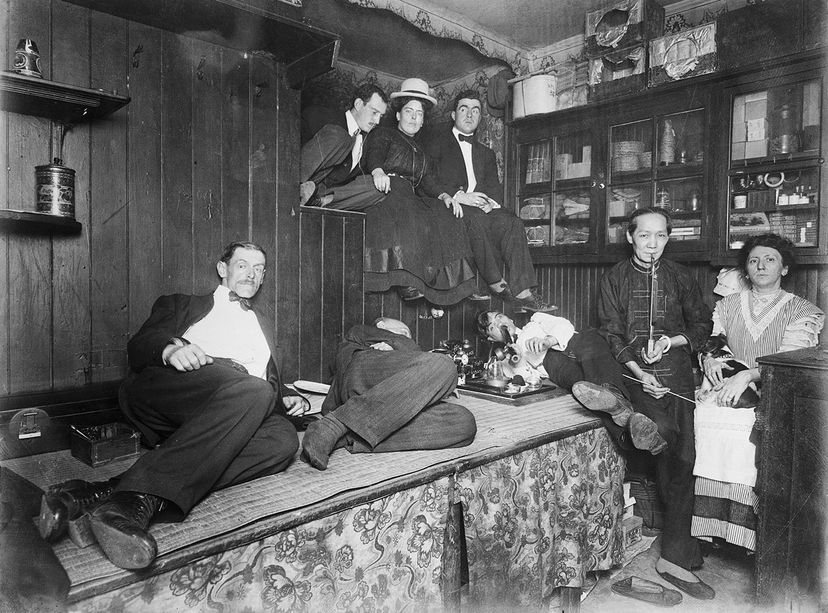

On a social level and cultural, they also saw Chinese restaurants as a menace to white women, whom they feared would be seduced by Chinese men who would take advantage of an assumed inherent female weakness, or maybe even conspire to get white women hooked on opium.

"[Non-Chinese American] cooks and waiters and restaurant owners really wanted the Chinese restaurants gone," says University of California, Davis law school professor Gabriel "Jack" Chin, via email. Chin co-wrote the article with John Ormonde. "But what got the labor movement as a whole interested was restricting immigration in general, and keeping Asians out of the workforce."

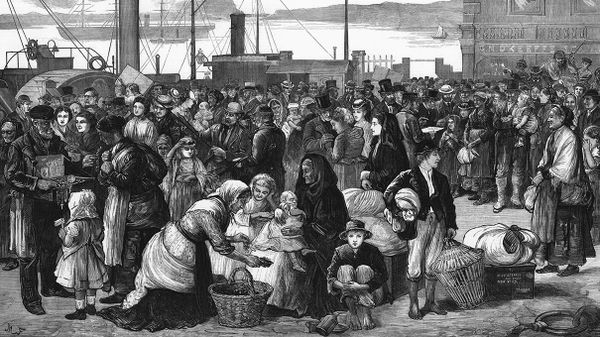

The movement to eliminate Chinese restaurants was part of a larger xenophobia directed against Chinese immigrants, who began immigrating to the U.S. in the 1850s to work in mining, agriculture and factories and played an important role in building railroads in the American West. Eventually, they started opening their own businesses, including restaurants such as California's inexpensive "chop suey houses," which sold a stir-fried mix of meat, vegetables, and eggs over rice or noodles.

Prejudice against and fear of Chinese immigrants led Congress to pass a series of laws that blocked Chinese immigration, starting with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

As this 2005 Slate article details, early Chinese restauranteurs apparently were eager to assimilate, to the point of including familiar American foods, such as grilled steak and roast chicken, on their menus.

But as Chin and Ormonde document, that didn't stop opponents from going after Chinese restaurants and trying to put them out of business through a variety of tactics. In some communities in the West, white union members simply threatened the Chinese restaurateurs to leave town — or else. They also organized boycotts and adopted resolutions shunning the Chinese, such as a 1915 recommendation adopted by a hotel, restaurant and bartending union dictating that "no members of our International Union be permitted to work with Asiatics."

"Unions, it is fair to say, were leaders in generating anti-Asian animus," says Chin. "They felt threatened."

When the boycotts weren't enough to keep away customers, opponents of Chinese restaurants tried another tactic. After a female missionary named Elsie Sigel was found murdered in a room above a Chinese restaurant in New York City in 1909, they lobbied for laws that banned white women from both both being employed by Chinese restaurants and even patronizing them as customers.

In some places, such as Washington, D.C., and New York City, the police didn't wait for ordinances to officially pass; they simply began forbidding white females from entering Chinese restaurants and nightclubs. Sensationalistic newspaper and magazine articles, which depicted Chinese establishments as dens of drug-fueled interracial debauchery, helped fuel the hysteria. (An added layer of irony is that the nation's opium dens, though often operated by Chinese and Chinese-Americans, were primarily visited by white Americans.)

The opponents weren't successful in ridding their cities of Chinese restaurants, and the organized movement against the eateries began to fade. That's partially due to bans on Chinese immigration; the Immigration Act of 1924, for instance, built upon the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act's ban on Chinese laborers by completely excluding immigrants from Asia. These laws provided a sense of security for the dominant white majority worried about jobs and revenue being "taken" from white Americans.

"Asians were not going to be a labor threat" after those bans, says Chin.

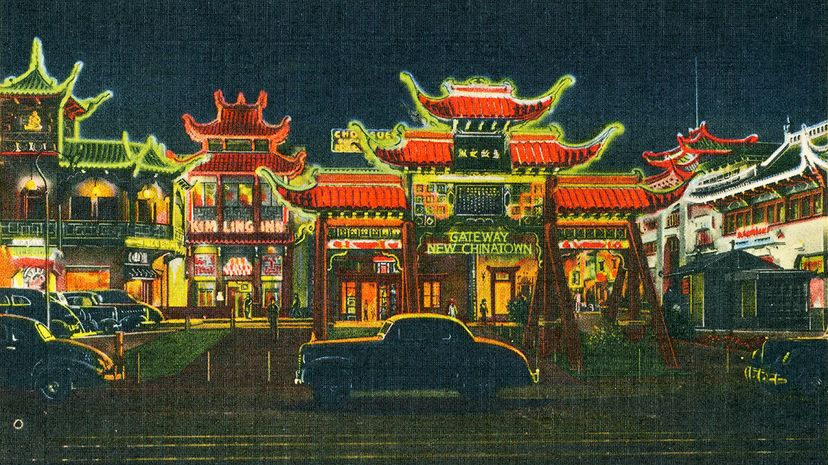

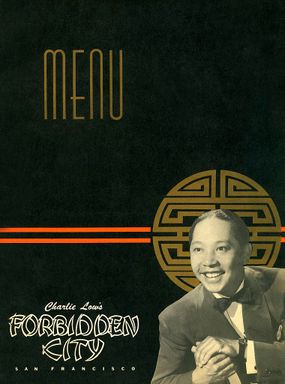

Eventually, though, Americans' taste buds won out over prejudice. In the 1940s, celebrities like Bob Hope and Ronald Reagan patronized Charlie Low's Forbidden City, a glamorous restaurant and nightclub in San Francisco's Chinatown neighborhood. And according to the National Archives, it wasn't until 1943 that the U.S. lifted the ban on Chinese people becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. Even after that, immigration laws made it difficult for people of Chinese origin to immigrate to the United States until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted — which didn't happen until 1968.

As food historian Andrew Coe details in "Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States," Chinese restaurants experienced a resurgence across the country starting in the mid-1960s. Noted chefs, particularly from Taiwan, began plying their trade in restaurants both upscale and more humble, and New York Times food writer Craig Claiborne became an enthusiastic booster of Chinese cuisine. In the decades that followed, Chinese food went from being considered exotic, invasive and corrupting, to become a staple across the country.

But while Chinese restaurants serving regional fare like Sichuan or Cantonese, or more mainstream American-Chinese interpretations, are now a widespread, that doesn't mean the United States is free of unease about immigrants. The authors of the paper say they see echoes of the early 20th century today.

"There is a long tradition in the United States of good things being reserved for white folks, and misguided economic race-tinged xenophobia," says Chin. "The waves of discrimination have always proved to be unnecessary, and counterproductive. The modern analogy is Mexican immigrants, who make a huge economic and cultural contribution, and sometimes find themselves deported from what used to be their own country."

Advertisement