The German zeppelin Hindenburg, the largest airship ever built, exploded and crashed while attempting to land at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, N.J., on May 6, 1937.

Advertisement

The Hindenburg had safely made 10 round-trip flights between Germany and the U.S. before its disastrous final journey. Here, the Hindenburg is in Frankfurt, Germany, after completing a record 48 hours in the air, May 15, 1936.

The Hindenburg was a luxury airship, capable of carrying people and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean in a comfortable two-day journey. The only other realistic option for crossing the ocean at the time was on an ocean liner, which was more spacious but took about a week. Here, the Hindenburg flies over New York City on its way to Lakehurst, N.J.

The interior of the Hindenburg included a number of passenger amenities, including a dining room, a lounge with a lightweight grand piano, a promenade with views of the world below, and a smoking room, which was pressurized to keep flammable hydrogen away from open flame. Here, a bartender stands behind the Hindenburg's bar.

The Hindenburg's control and navigation rooms were housed in a cabin under the ship. This is a view of the Hindenburg's cockpit.

Advertisement

Airship landings were treacherous affairs, requiring the crew onboard to precisely level the craft while men on the ground used mooring lines to pull it in safely. Gusts of wind could send airships aloft again, leaving the men to choose between hanging on and falling, either of which could lead to injury or death. Here, ground crew members struggle to stabilize the Hindenburg as it enters its moorings after a flight on May 20, 1936.

On May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg caught fire while landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station. Thirty-five of the 97 people aboard were killed, along with one person on the ground.

Although the exact cause of the explosion has never been determined, the general consensus is that a spark ignited the hydrogen gas that kept the Hindenburg afloat. The Hindenburg was made to use helium rather than hydrogen, which was much safer but also heavier. However, Germany didn't have enough helium to fill the airship and had to use hydrogen instead.

The paint, also known as dope, used to make the skin of the Hindenburg waterproof helped the fire spread. The dope contained iron oxide and aluminum powder, which combine to form thermite. The entire ship was engulfed in flame in 34 seconds.

People onboard leapt from windows and catwalks to escape the flames. Members of the ground crew fled from the crashing vessel, then returned to try to pull survivors from the wreckage.

Advertisement

Of the 97 people onboard, 62 survived, although many of the survivors were severely injured. The disaster followed several other airship crashes in the 1920s and '30s and effectively put an end to commercial airship travel.

A solitary soldier guards the remains of the Hindenburg. An extensive investigation followed the crash to determine whether the explosion was the product of sabotage, most likely in protest of the Nazi government. Sabotage has never been proven.

At the scene of the crash, Department of Commerce inspectors George W. Lossow (left, hat and grey coat) and J. E. Sommers (dark coat, uncovered) examine the forward port motor of the Hindenburg on May 20, 1937. Other vital parts are covered to protect them for later inspection.

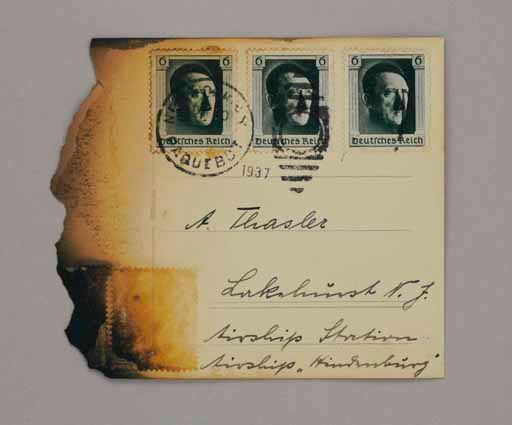

In addition to carrying people, the Hindenburg carried mail and other cargo. This postcard was salvaged from the wreckage.

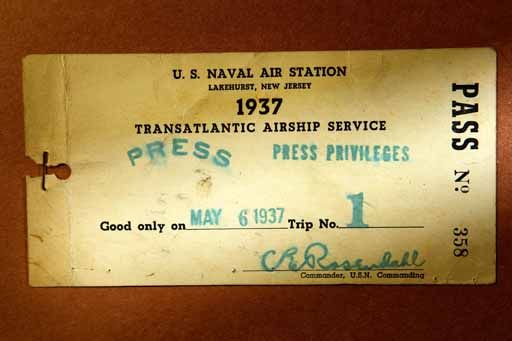

The Hindenburg's final flight was its return to service after being refitted over the winter, which is why reporters were waiting at Lakehurst. This press pass belonged to Arthur Cofod, a courier sent to pick up photos being delivered on the airship for Life Magazine. Cofod used his own Leica camera to record the disaster, and his photographs ended up being published in Life. The coverage of the disaster also included Herb Morrison's famous "Oh, the humanity," which was recorded for Chicago radio station WLS and aired coast-to-coast via NBC.

Advertisement