Eggs aren't a dime a dozen, but they aren't exactly in short supply, either. It's difficult to imagine fighting over an egg, right? This is exactly what happened in the Great Farallones Egg War of 1863, a time when people went to, ahem, great "eggstremes" to secure eggs.

They weren't fighting over ordinary chicken eggs, though. We're talking about the eggs of the common murre (Uria aalge) a penguin-like bird that nests on rocky cliffs and spends its winters at sea. During its breeding season, which runs May to July, the birds lay spotted, pointy eggs about twice as big as a chicken egg. The blotchy patterns make it easier for birds to identify their eggs among the thousands that dot the rocks, while the pointed design ensures the egg will spin in a circle if it rolls out of the nest, rather than falling into the sea.

Advertisement

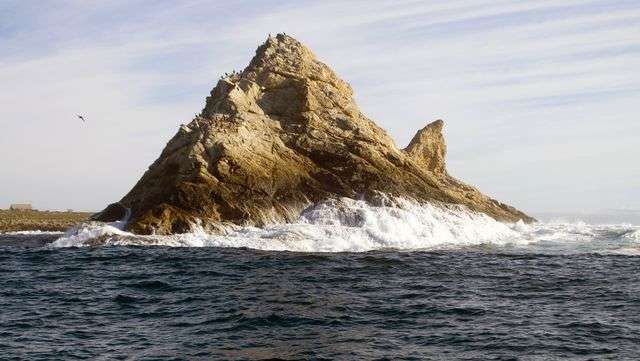

And it just so happens that 150 years ago, the common murres' favorite egg-laying perch in the Lower 48 was just off the coast of San Francisco. The Farallones Islands are a series of small outcroppings of jagged granite upshoots about 27 miles (43.5 kilometers) from San Francisco's coastline. The birds land by the thousands on the islands, nesting wing-to-wing and dotting the landscape with egg after egg.

By the time the California Gold Rush overburdened then-tiny San Francisco with a largely unsupervised milieu of hungry miners and equally profit-hungry businesses, the area's common murres numbered into the tens of thousands—perhaps into the millions. And their eggs were ripe for the picking.

Six men decided to profit from the birds' efforts. In 1851, they sailed to the islands and gave themselves ownership, complete with company shares. But it wasn't easy to gather the eggs. They had to climb steep cliffs slick with sea spray while being swarmed by murres and many other seabirds that called the islands home, but evened the odds by stomping on day-old eggs to ensure only the freshest were gathered. Still, they persevered and the Egg Company began making a sizable profit selling the freely collected common murre eggs to San Francisco bakers.

"Common murre eggs were an incredibly abundant resource at a time when San Francisco was overwhelmed by people flooding in," says Gerry McChesney, manager of the Farallon National Wildlife Refuge and its common murre program. "San Francisco not only lacked the infrastructure it needed, but there were no chicken farms to supply such a great need."

By the early 1860s, the Egg Company had some serious competition. Its hold on the islands was tentative at best. Four year earlier, U.S. president James Buchanan solidified the federal government's own claim to the land for a lighthouse. And then on a summer day in 1863, 27 armed challengers sailed toward the island. When their three boats attempted to land, the Egg Company foreman warned them off, but the interlopers declared they intended to land "in spite of hell."

What came next? The Egg Company owners opened fire. And when the challengers fired back, one of the Egg Co. men was killed after being shot through the stomach and heart. The Egg Co. men then fired on and wounded five of the men in boats, who after 20 minutes of war, sailed back to home base. One of the injured men, shot near his throat, died a few days later.

The post-Gold Rush tension, although not as dramatic, continued for years until commercial egging was banned in 1896 after the California Academy of Scientists successfully lobbied for its end. In the late 1960s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began managing the islands and protecting common murre breeding areas. Even so, the consequences of commercial egging still echo today.

"It had a long-term, devastating impact on the murre population," McChesney says. "It's still recovering."

There are now about 300,000 common murre that travel to the islands for nesting season, McChesney adds, still fewer than it had before the Gold Rush more than a century and a half ago.

"It is something I never get tired of watching," he says of the bird groups. "The islands themselves are beautiful, rugged and otherworldly. But to be out there during the peak of the breeding season? It's a spectacle to behold."

Advertisement