Jones himself was a puzzling figure. As this 1978 New York Times biographical sketch describes, he was born in 1931 in Lynn, Indiana, a rural town so small that it had a single traffic light, where one of the main businesses was making coffins. He was the son of a World War I veteran who had difficulty making a steady living, and a mother who worked in factories and as a waitress to make ends meet. Jones' mother pushed him to make something of himself and he eventually enrolled in Indiana University with the plan of eventually becoming a doctor.

But after Jones joined a fundamentalist Christian church in Indianapolis, he abandoned his medical ambitions, and instead decided to become a minister. According to the Times, he saw religion as a way to organize people to achieve change and fix social problems such as racial discrimination and poverty. In 1953, he left the white congregation that he originally joined and established his own church, which he opened to all ethnic groups. Low on funds, Jones supported himself and his religious organization with an exotic sideline: He imported monkeys and went from door to door to sell them as pets for $29 apiece.

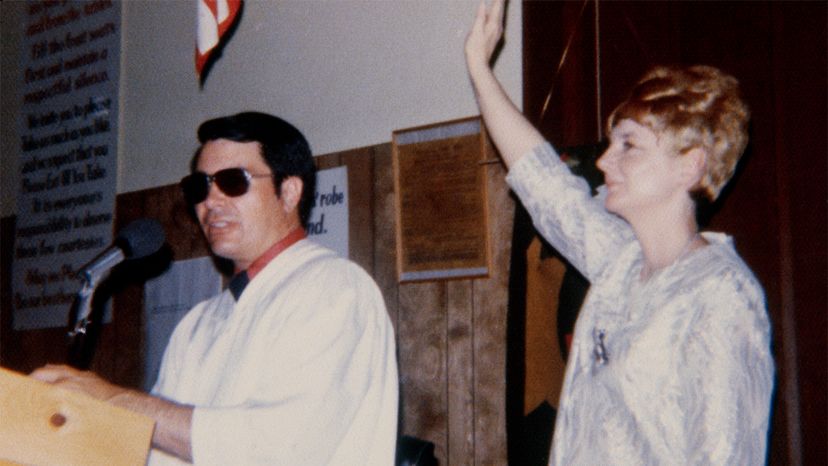

Jones' congregation in Indianapolis grew, and he eventually attracted hundreds of followers, according to the Times account. He made a reputation for himself by opening soup kitchens and helping poor people — both Blacks and whites — to find jobs, and for a time served as the city's Human Relations Commissioner. At the same time, though, he also became fascinated with Father Divine, a flamboyant, flashy-dressing Depression-era preacher who mixed bits and pieces of various religions to forge a movement that operated scores of restaurants, gas stations, hotels and other businesses. Jones was impressed by the loyalty of Father Divine's followers, and decided to reshape his own image in imitation. Jones also started conducting faith healings, claiming that he could miraculously cure people who suffered from cancer and arthritis.

After Jones came under scrutiny in Indianapolis for real estate transfers made by church members to a corporation that Jones and family members controlled, his preaching took a darker, apocalyptic tone. He warned his followers that a nuclear war would occur within a few years, and that they needed to move with him to a supposedly safer place — northern California.

In 1965, he led 70 families to relocate with him there in a rural town in Mendocino County. But by the early 1970s, Jones decided that his real calling was preaching in low-income Black resident in the cities. He opened a church in San Francisco and eventually, a second branch in Los Angeles. Jones' blend of social activism and his seemingly tireless organizing efforts bore fruit. At his peak, he claimed to have 20,000 followers, the Times reported.

While people were attracted to Jones by idealism, they gradually were drawn into a cult that became increasingly extreme. One psychology textbook cites Jones as an example of narcissistic personality disorder, in which a person has an inflated sense of importance and a craving for admiration, coupled by a lack of empathy and intolerance to the slightest criticism. To exacerbate matters, Jones also became addicted to pharmaceutical drugs — and used them heavily that his autopsy revealed tissue levels of pentobarbital, a tranquillizer, that were "within the toxic range."

Jones gave marathon sermons that sometimes lasted six hours, and made his followers work so hard that they became too tired to complain — or too afraid of his "catharsis sessions," in which participants had to confess personal secrets at the risk of being beaten with a paddle. There were rumors of members being forced to sell their homes and turn over their savings to the church.

"It's a mistake to think that Jim Jones was all one thing or another — a skillful manipulator or an extreme personality," investigative journalist Jeff Guinn says via email. He's the author of the 2018 book "The Road to Jonestown," and executive producer of the Sundance TV docuseries "Jonestown: Terror in the Jungle."

Jones "was always something of both. Over the years drugs and hubris pushed him ever closer to the extreme aspects of his psyche," Guinn says.