In November 1942, Winston Churchill delivered a speech to the British House of Commons that laid bare the Allied strategy for defeating Nazi Germany and its Axis sidekick in Europe, Italy. The Allies would first take Northern Africa, then invade Europe through "the underbelly of the Axis, especially Italy," said Churchill. (He didn't call it the "soft underbelly," by the way — that's a misquotation.)

If Adolf Hitler wanted to know precisely where the Allies were going to attack, all he had to do was look at a map of the Mediterranean. The Allies would almost certainly launch their invasion from Northern Africa, and the closest Axis target by far was Sicily, the southern Italian island.

Advertisement

And that's exactly what happened. In July 1943, British and American troops carried out a wildly successful amphibious invasion of Sicily, encountering limited resistance from the Italian forces. Within months, Italy surrendered.

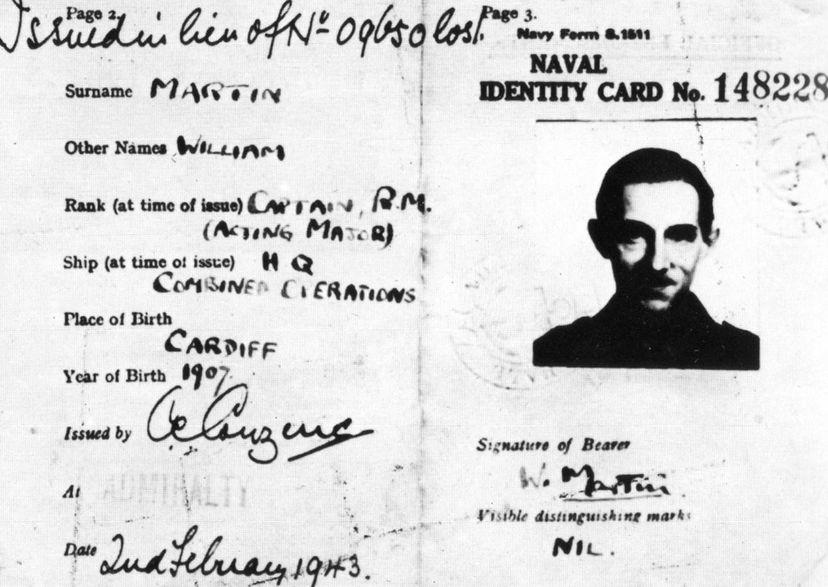

But if Hitler knew back in 1942 that the Allies were going to invade Sicily, why was it left nearly defenseless? Because of a brilliant and risky top-secret plot known as "Operation Mincemeat." Born from the mind of Ian Fleming — the James Bond creator who worked in British naval intelligence during World War II — Operation Mincemeat dared to fool the Fuhrer into believing that the Allies were going to invade Greece instead of Sicily.

All it took was a dead body, some falsified documents and a lot of luck.

Advertisement