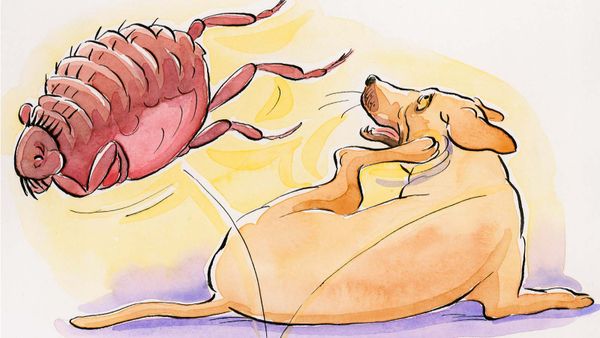

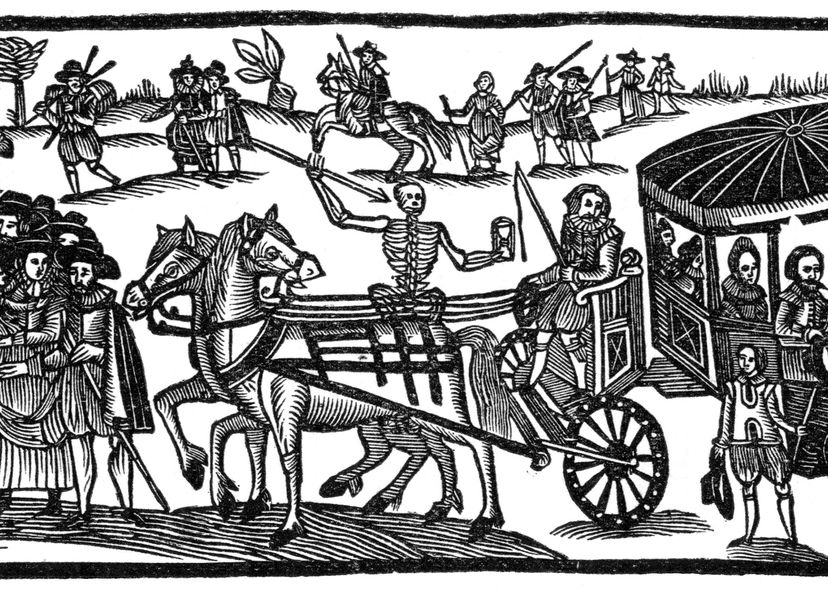

In the 17th century, a return of plague — also known as the black death — killed about 1 million people in France. Oddly enough, the residents of Paris were largely unaffected, despite having the same rat problem as any other large city. The rodents carried fleas that bore the plague. After the plague killed the rats, the fleas often hopped onto human hosts. In this way, the plague spread like wildfire, snuffing out life after life.

The Parisians' miraculous avoidance of the plague could have remained one of history's mysteries, but author Tom Nealon squeezed a potential explanation out of seemingly disparate events. A purveyor of rare books, Nealon is not only a connoisseur of history, but of the impact condiments and foodstuffs may have had on antiquity. His new book "Food Fights and Culture Wars" follows the sometimes-surprising influence food has had throughout history.

Advertisement

"Health and food were intimately connected for the longest time," says Nealon. "Early collections of recipes frequently mixed medical and cookery receipts (as recipes were called), so it's easy to start to conflate them when you are studying the period and old cookbooks. Even after they started to separate, the Renaissance 'Book of Secrets' kept elements of food and home remedies together for centuries longer."

In the case of Paris and its largely unscathed population in the 1600s, the timing of a lemonade trend and the timing of a plague coincided. "I started to wonder what a relationship between the two might be," says Nealon.

Advertisement