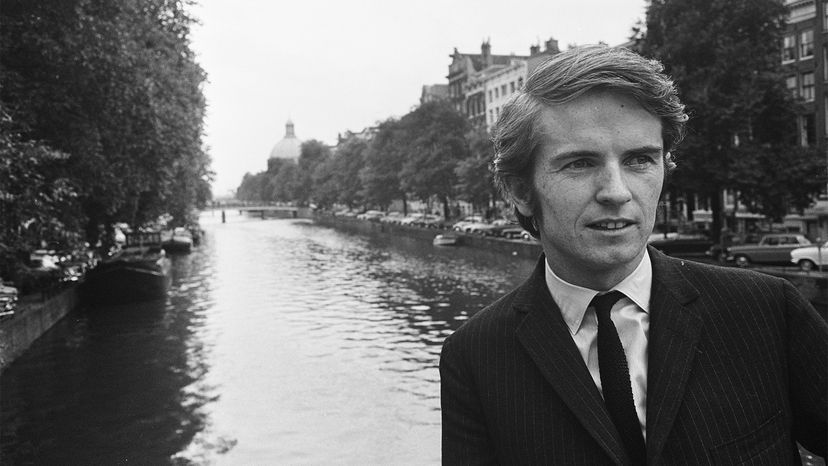

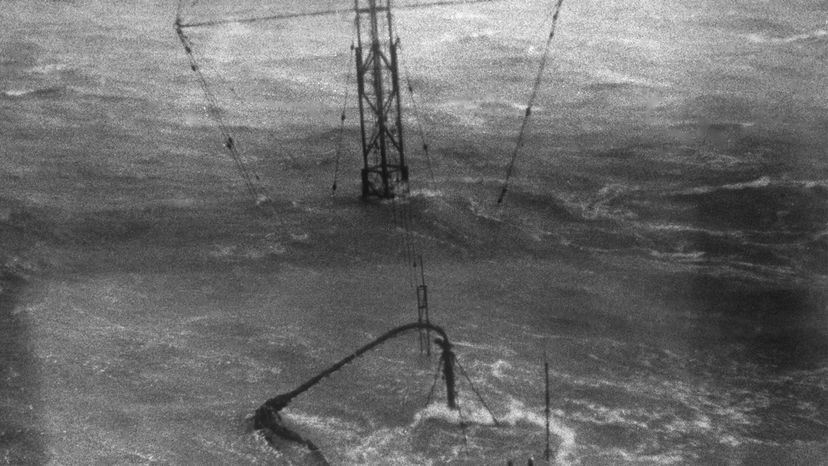

If you've been binge-watching movies lately, you may have come across "Pirate Radio." Director Richard Curtis' 2009 comedy-drama stars the late Philip Seymour Hoffman as The Count, a disc jockey for an unlicensed rock radio station that broadcast from a rusty, decrepit ship off the British coast in the mid-1960s, defying government authorities to spin the rock records that weren't allowed on the BBC at the time. The plot is based loosely on the saga of an actual former pirate station, Radio Caroline, that was founded by an offbeat Irish entrepreneur named Ronan O'Rahilly, the inspiration for the character portrayed by Bill Nighy.

"Pirate Radio" is a period piece, set in a time when the Rolling Stones' "Let's Spend the Night Together" and the Who's "My Generation" were still scandalous and controversial rather than nostalgic anthems for today's aging baby boomers. So you couldn't be blamed for assuming that it depicts a long-vanished phenomenon, like Nehru jackets with iridescent scarves and psychedelic-patterned paper mini dresses.

Advertisement

To the contrary, though, more than a half-century later, pirate radio is still a thing. In fact, it's possibly more widespread than it was in the 1960s, even in an age when streaming internet services such as Spotify and Pandora put the equivalent of a jukebox in the pocket of everyone with a smartphone. And as a bonus, Radio Caroline still exists — though, ironically, it's gone legal.

In the U.S., pirate stations have popped up in recent years all over the country, from West Virginia to Washington state, according to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which plays a continual game of whack-a-mole in an effort to keep them off the airwaves used by licensed broadcasters. Unauthorized stations are particularly prolific in the New York City area, where a 2016 study by the New York State Broadcasters Association (NYSBA) found that there actually were more pirates then on the FM band than legal licensed stations.

"Pirate radio continues to exist in the internet age for a variety of reasons," John Nathan Anderson, a broadcasting scholar and author who is working on a book about pirate radio, explains via email. "One is cost. It's eminently cheaper to purchase or build an unlicensed radio station than it is to set up a robust streaming channel online, especially if you're looking to cover a local area. All you need is a location to host the antenna and access to electricity — unless you've got batteries, then just the location."

Additionally, pirate broadcasters don't have to deal with all the legal complexities of setting up and running a streaming internet service, such as writing terms of service or meeting contractual obligations, he notes. And audiences can get the station on inexpensive radio receivers — there's no need to have a computer or a smartphone with 5G, or to pay a monthly subscription fee or worry about blowing through their data limits. They just twist the dial. Very old school, and cheap enough for anyone's budget.

Thanks to e-commerce, it's also easier than ever for a would-be pirate to find the necessary equipment and have it delivered to his or her door, as FCC enforcement official David Dombrowski described in this 2019 podcast. Powerful, uncertified transmitters manufactured in foreign countries easily slip through customs at U.S. ports.

Advertisement