It's quite a conundrum: needing to conduct research on people who don't know you're conducting research on them. But that was the predicament in which researchers Mary Henle and Marian B. Hubbell found themselves in back in the 1930s.

As part of Henle's psychology graduate work, Henle and Hubbell were trying to determine whether children became less egocentric as they grew older. In order for the researchers to get a real feel for the conversations of college students, they took to any means necessary.

Advertisement

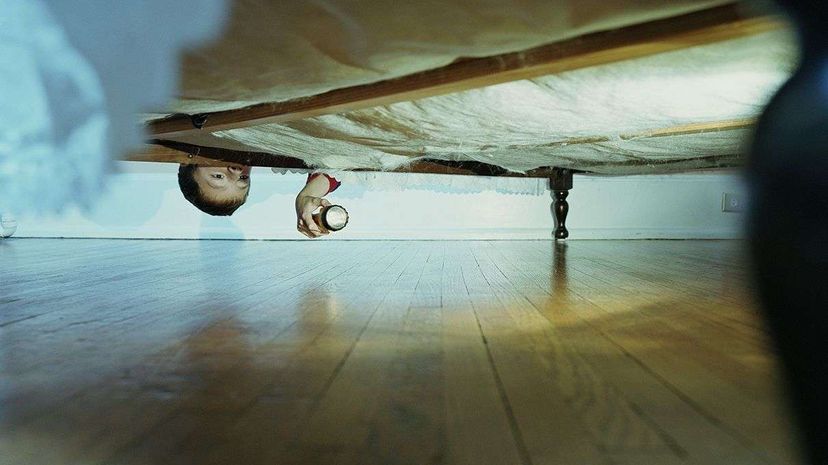

According to the study, in order to prevent knowledge of their presence "they concealed themselves under beds in students' rooms where tea parties were being held, eavesdropped in dormitory smoking-rooms and dormitory wash-rooms, and listened to telephone conversations."

The researchers didn't confine themselves just to the campus though. They also captured remarks in waiting rooms, hotel lobbies, theaters and restaurants. Even on the streetcar. They pursued their unsuspecting subjects in the streets, in department stores and into their homes. In each case, the researchers jotted down a verbatim record of the remarks on the scene.

Dr. Ali Mattu is a clinical psychologist who hosts "The Psych Show," and he emailed us to shed some light on the context of this experiment: "The hallmark of psychological science is experimentation — highly controlling an environment and only manipulating one experimental variable. While this type of research can tell us a lot about the relationship between cause and effect, experimental studies can sometimes lack external validity."

Which is to say, the more control a researcher exerts on an experiment, the less it seems like real life, Mattu explains. Observational studies, like the one Henle and Hubbell carried out, pose a way to mitigate that effect, although they have their own drawbacks. The duo hoped to get good data without the biasing effect of letting their subjects know they were being observed.

Why? Because knowing you're being observed changes your behavior.

"This is called objective self-awareness," Mattu tells us. "This can be helpful in a lot of situations. Banks and other high security environments show you security camera footage of yourself to trigger objective self-awareness and reduce the chances you might do something stupid. For the purposes of research, knowing that you are being observed can lead to reactivity. People might act the way they think an experimenter wants them to act. Or they might act more in line with cultural expectations. They might also act the opposite of what is expected, because they know this is an artificial situation."

Back in Henle and Hubbell's time, though, the concept of objective self-awareness hadn't been defined. And they also lacked something else critical to research studies today: informed consent. That would arise from the Nuremberg Code after World War II.

"The rules now state that people must be fully aware of an experiments risks and benefits before they sign on to participate," notes Mattu. "Additionally, you cannot involve anyone in any type of research without their complete consent. And if at any time they want to pull out of a study, they can."

Scientists could do a sort of modern take on Henle and Hubbell's experiment today, but in a much more controlled and ethical way. All research has to go through institutional review boards that work to protect participants from studies that would have scientists hiding under beds.

"Researchers can easily study behavior in public spaces without getting informed consent from others as long as they don't reveal any identifying information about the people being observed," Mattu says. "Researchers typically do this by showing results in aggregate. For example, someone studying public behavior in Times Square could describe how many times people help each other out as long as they don't describe specifics of individuals."

If the authors of the 1938 study wanted to get their results today, their methodology would need to be drastically different to conform to ethical standards.

Though they arrived at their results by dubious means, Henle and Hubbell found that adults don't shed their egocentricity after all.

And they had a lot of time to think about it, hiding under beds and sneaking around campus.

Advertisement