What if you could travel anywhere on Earth at a moment's notice? And what if you could choose not just the destination but also the time period? Instead of spending a lot of money and time trying to get to a distant city, you could explore the site at any point in its history. That's one of the promises of virtual reality.

Back in the early 1990s, when the term virtual reality was just getting popular, the sky was the limit. Hollywood created outlandish visualizations of what computing would look like — it seemed even the simplest of computer tasks would involve jumping into a virtual world. As people discovered that the technology wasn't nearly as sophisticated as what we expected, interest in VR quickly died out among the public. But it remained strong in certain circles. Like academia.

Advertisement

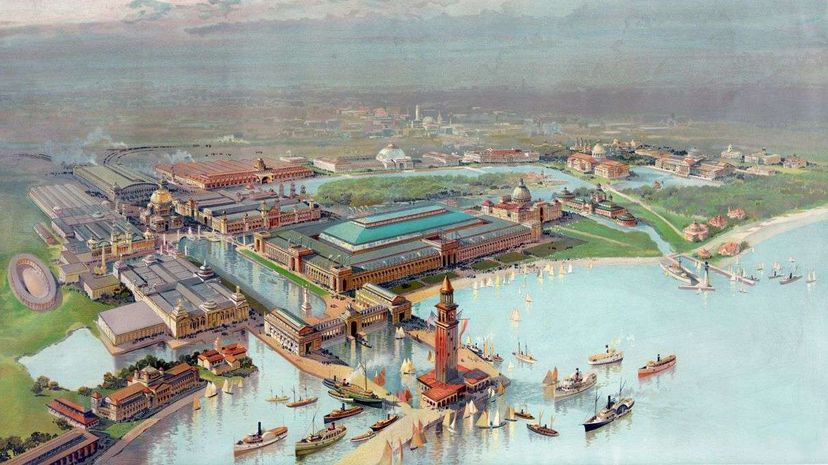

At UCLA's Institute for Digital Research and Education, there's a department called the Urban Simulation Team. As the name implies, the team's purpose is to build virtual simulations of actual urban environments. One of the high-profile projects the team has pursued is a virtual model of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, also known as the World's Columbian Exposition.

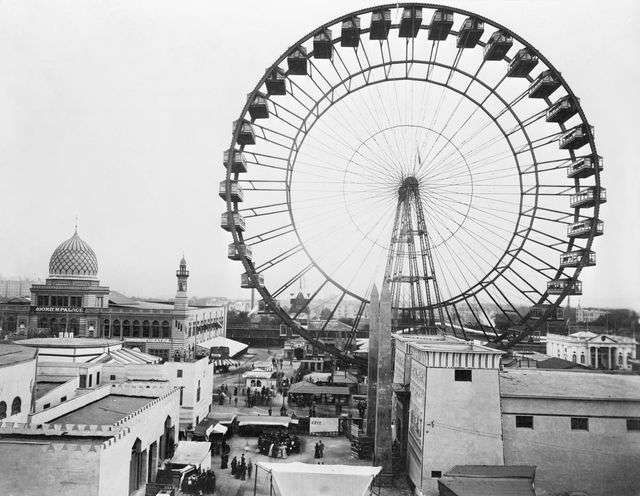

The fair was a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus arriving in the New World. The exposition was enormous — consisting of 633 acres (256 hectares) of buildings, ponds, gardens and fairgrounds specifically built for the fair itself. Of all those buildings, only one remains, and it serves as the current Museum of Science and Industry. The team has showcased the virtual model at the museum a few times, presenting updated models and giving the public a chance to explore a Chicago of the past.

Descriptions and photographs of the World's Fair are sure to inspire daydreams of what it must've been like to explore the fairgrounds. But with virtual models, you don't have to imagine. The team has worked to create an accurate representation of what the grounds looked like. It's all to scale, and you can virtually explore the area, even going into some buildings.

The team does its best to build out the fair according to available information. In some areas, that's not possible simply due to a lack of photographs and other information. A row of shops might include some placeholders rather than actual stores that were at the fair, for example. The project is ongoing, and designer Lisa Snyder says she suspects that there's enough work left to take up the rest of her life. She's already spent nearly two decades on the project.

Snyder's team shows what happens when you merge multiple disciplines to create something new. Historical research — Snyder estimates it takes five hours of research for every hour spent working on the computer model — and virtual design can create an experience that allows us to appreciate a time and place in a new way. Imagine using a similar approach for other times and places. The history classroom of tomorrow may look more like a computer lab than a lecture hall.

Advertisement