What could you do to help those fighting in a brutal war? At some points in history, whole nations of individuals have had to ask themselves that question: They've rationed food and supplies, restructured their careers, nursed the wounded soldiers themselves, and even monitored their own everyday speech. During World War I, an American woman named Anna Coleman Ladd used her skills as an artist to change the lives of men disfigured in the war in a profound way.

WWI was fought differently from any war that preceded it. The 20th century brought with it the fruits of the Industrial Revolution, which, in this case, included machine guns. Soldiers were often dodging a hailstorm of bullets rather than single shots — and artillery, which involved lots and lots of shrapnel. Around 21 million men were injured in the war, and though many of them went home with all their arms and legs, some of them lost chins, noses, lips and cheekbones — not surprising since trench warfare involved a lot of looking up over the edge of the trench to see if the coast was clear. Facial reconstruction surgery was a brand new technology at this time, and though some of its practitioners had experience fixing small facial deformities, the plastic surgeons were suddenly presented with the daunting task of reconstructing entire faces.

Advertisement

"Within the surgical and convalescent wards, it was grimly accepted that facial disfigurement was the most traumatic of the multitude of horrific damages the war inflicted," wrote journalist Caroline Alexander.

Anna Coleman Ladd was an American sculptor from Boston who moved to France during WWI so her husband could take a position with the Red Cross. After learning about the plight of these men and corresponding with English sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, the founder of the Tin Noses Shop in London, where he made tin masks for soldiers with facial mutilations, Ladd, with the help of the Red Cross, set up her own studio in Paris called the Studio for Portrait Masks.

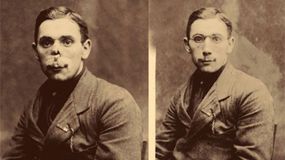

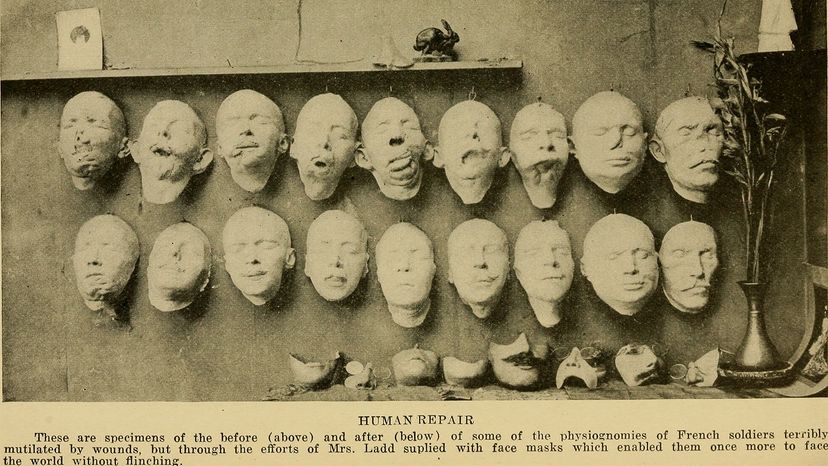

Ladd turned out to have real gift for crafting portrait masks. Precursors to today's facial prosthetics, the masks were created to cover just the damaged portion of the soldier's face (which could, of course, sometimes include the entire face). Ladd's work was lauded as the best of its kind, and each mask took months to produce. This silent video shows actual footage of Ladd and her assistants at work in the studio:

In order to create a mask that resembled the each man's pre-war face as closely as possible, Ladd first required photos of his original face, and after the wounds from his injury and any subsequent surgery healed completely, she and her team got to work. She took a plaster cast of his entire face (which must have been a nightmarish, suffocating ordeal for her client), and from there, squeezes — clay or plasticine copies — of the cast, on which Ladd could base her subsequent portrait recreation work.

The masks themselves were made from very thin galvanized copper, about the thickness of the cover of a paperback, and they were usually held in place with spectacles. Ladd painted each mask with enamel while the man was wearing it so she could get the best possible skin-tone match. Facial hair like mustaches, eyelashes and eyebrows were added at the end with real hair. Although Ladd's studio was only open for a year, she and her four assistants created 185 masks, which changed the lives of her clients — they were able to live with their families, get jobs and feel as if they belonged, rather than hiding away, feeling monstrous in a veteran's home.

Ladd was a pioneer in facial prosthetics, and her results were remarkable, even though the masks were fragile and easily battered, and they didn't restore movement and function to the face. These days, facial prosthetics are used in situations in which surgical reconstruction isn't technically possible or isn't recommended for the patient for other reasons.

"There are many reasons why a patient cannot have a surgical option offered to them," says Juan Garcia, an anaplastologist at the Johns Hopkins Carnegie Center for Surgical Innovation. "A person missing an eye and eyelids cannot have this reconstructed, cancer patients who undergo radiation therapy do not heal well, surgical reconstruction of the ear and nose is very delicate surgery, oftentimes leading to a poor aesthetic outcome even in the hands of a skilled surgeon."

Modern anaplastologists still work with plaster and paint, but they use modern dental materials like resin die stone — an ultra-strong form of gypsum that behaves a lot like plaster — and paints mixed with silicone.

"Unlike the painted rigid masks made of copper that Ladd made, we generally sculpt the prosthetic device in wax before the stone mold is made to cast a soft, flesh-like silicone prosthesis," says Garcia. "These days we use advanced digital technologies such as surface scanning, digital sculpting and 3D printing, and implants in the form of titanium screws, similar but shorter than dental implants. These screws are placed into the bone by a surgeon and can be used to hold the prosthesis in place."

So, nobody's holding their prosthesis on by dangling it from some spectacles anymore. But Ladd paved the way for a lot of the good work anaplastologists do today, and the outcome is largely the same:

"The work of the anaplastologist allows patients to get back to their work, family, friends, and activities they enjoy," says Garcia. "It allows them to move forward with their lives with a renewed sense of normalcy, albeit a 'new normal.' Hopefully the work goes undetected, however, the main goal is to help the patient move from an isolated and perhaps ostracized state, to one where they can once again engage others."

Advertisement