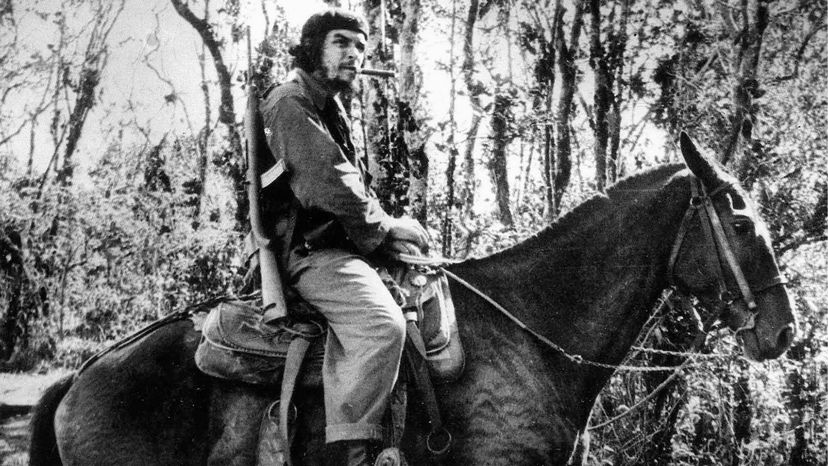

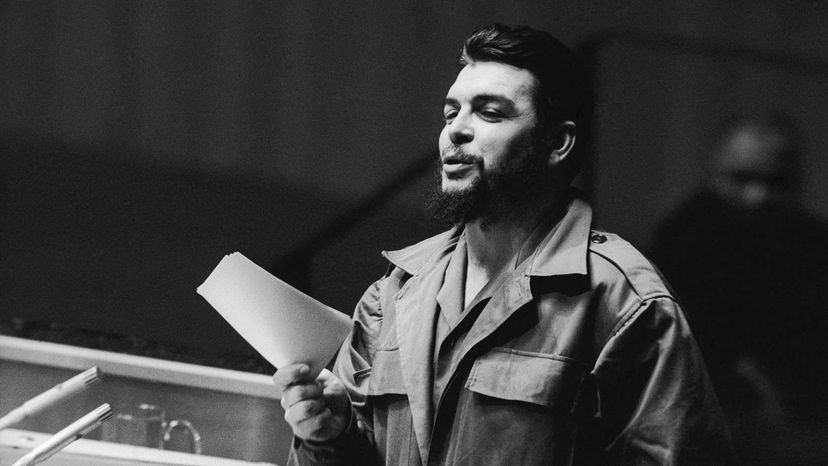

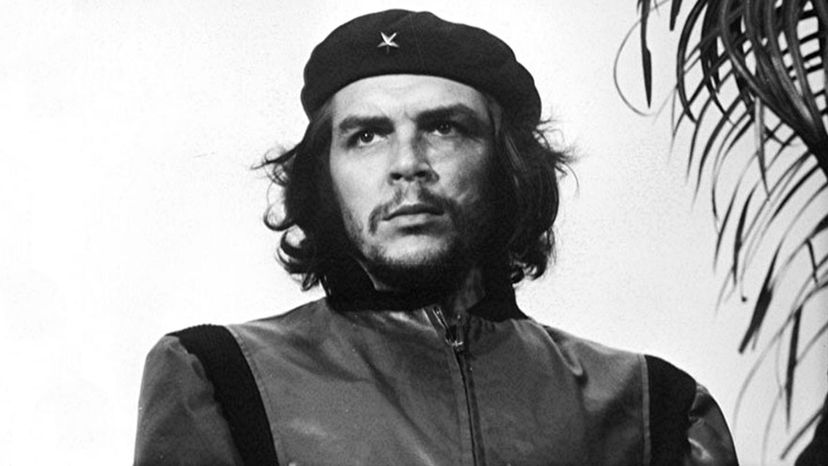

As the literal face of revolution, Ernesto Guevara — you probably know him by his familiar nom de guerre, Che — is hard to miss. His bearded, semi-beatific mug can be found anywhere that people long to bring down oppressors and prop up the little guy. And in a lot of places, too, where it's simply cool to wear Che on a T-shirt.

As a real flesh-and-blood revolutionary, though, Che Guevara was not all that. His short, clench-fisted life battling "the man" was littered with more defeat than victory, and pockmarked throughout (something his millions of admirers often forget) with some dastardly, decidedly unheroic criminal acts. Even his death, at age 39 in 1967, was in reality just sad and unceremonious, hardly the stuff of, say, Scottish hero William Wallace.

Advertisement

Still, in death, this unquestioned thorn in the status quo's side has become the inescapable symbol of everything that dreamers think a revolutionary should be: strong, principled, a threat to the rich and powerful, a champion of the weak, a leader of the downtrodden.

"In the course of my professional interest in revolution, I've been all over the world. Peru. Colombia. Mexico. Pakistan. Multiple trips to Afghanistan. Iraq. Cambodia. Southern Philippines. All over the place," says Gordon McCormick, who has taught a course on guerrilla warfare at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, for almost 30 years. "No matter where you go, you see photos of Che. This guy has an international appeal, particularly in Latin America. You can go down to Mexico and you see cars driving around with mudguards with his image on them. He's everywhere. He is a motivator for would-be revolutionaries the world over."

Advertisement