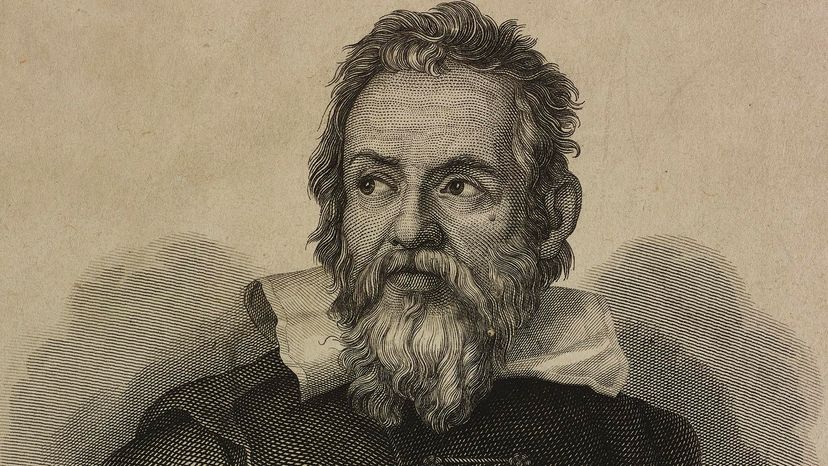

Today, Italian astronomer, physicist and author Galileo Galilei, who lived from 1564 to 1642, might be most famous for having been put on trial for heresy by the Roman Inquisition in 1633. That event has come to symbolize the conflict between adherence to religious dogma and the intellectual freedom required by science.

Galileo's trouble with authorities actually stemmed not from his own work, but from his advocacy of Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric theory that the sun, not the Earth, was the object around which the planets revolved. Galileo was forced to renounce those views to avoid torture and execution and had to spend the last years of his life under house arrest. Even so, Galileo ultimately won the argument. Three-and-a-half centuries later, Pope John Paul II gave a speech in which he not only said that the church's persecution of Galileo had been a mistake, but also praised him as a brilliant mind who "practically invented the experimental method."

Advertisement

But that brouhaha isn't the most important thing about Galileo, a scientific giant whose discoveries forever changed humans' view of both the cosmos and the physical world in which we live, and helped establish the way in which modern scientists do science. He also became one of the first celebrity scientist-authors, whose 1610 book "Starry Messenger" became a sensation.

"Galileo is an interesting example of a versatile Renaissance mind," explains Paula Findlen, the Ubaldo PIerotti Professor of Italian history and co-director of the Patrick Suppes Center for the History and Philosophy of Science at Stanford University, via email. "He loves literature, art and music as well as science. He knows how to draw and he certainly knows how to write with eloquence. He's fascinated with how things work and visits artisans to know more. I see him as one of the culminating products of the Renaissance living in the age of the Reformation. Yet what he does with his knowledge launches a new age of science and observation."

Advertisement