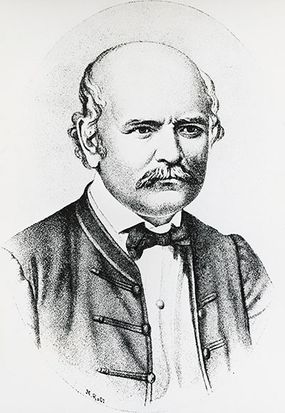

If ever you were frustrated with your mom because she constantly told you to wash your hands, remember this — it was because so many mothers died that hand-washing first became a thing. And that, dear reader, is how we begin the strange, sad story of Ignaz Semmelweis, a 19th-century doctor and father of infection control.

Semmelweis was born in Hungary in 1818, and after graduating from medical school, he started a job at Vienna General hospital (Austria) in 1846. There, he became aghast at the mortality rate of new mothers in a particular ward.

Advertisement

In this ward, up to 18 percent of new mothers were dying from what was then called childbed fever, or puerperal fever. Yet in another ward, where midwives – instead of doctors – delivered all the babies, only about 2 percent of mothers perished after childbirth, according to the British Medical Journal.

Semmelweis began reasoning his way to the root of the problem. He considered climate and crowding, but eventually ruled out those factors. In the end, the midwives themselves seemed to be the only real difference between the two wards.

Then, Semmelweis had an epiphany. One of the hospital's doctors, a pathologist named Jakub Kolletschka, accidentally nicked himself with a scalpel that he'd used during an autopsy of one of the unfortunate mothers. He was sickened with childbed fever and died.

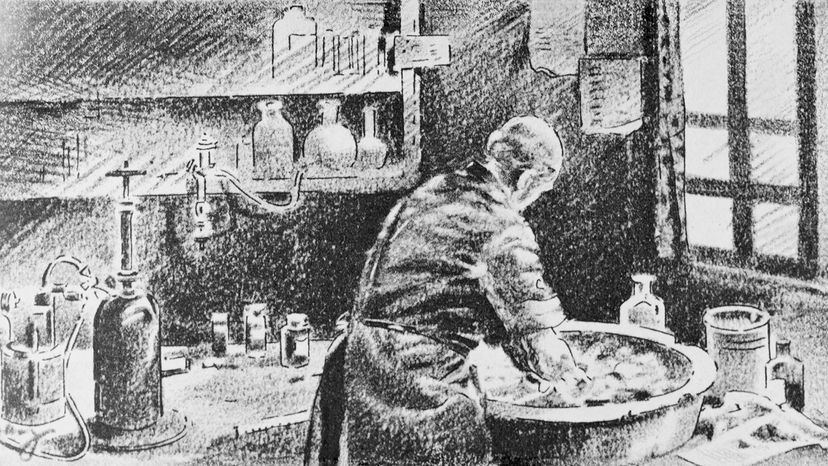

Semmelweis believe that the doctors were dissecting infected corpses and – cue gag reflex – immediately afterward, delivering babies, without stopping to wash their hands. He suspected that this was the source of the deadly problem.

"Basically, his hypothesis here was that it was cadaveric matter from the scalpel that entered Kolletschka's blood and caused the infection, and that same material could be transferred to the women on the hands of the doctors – because the doctors would do autopsies and then go straight to examine the women who had given birth, without washing their hands, changing their clothes or basically taking any hygienic measures at all," says Dana Tulodziecki, a philosophy professor at Purdue University via email.

"He then tested this hypothesis by requiring people who had performed autopsies to wash their hands with chloride of lime – a disinfectant – before attending the women and after this the mortality rate in the first clinic fell to that of the second."

You'd think that Semmelweis' fellow doctors would be lauding him for this discovery. But you'd be wrong.

Advertisement