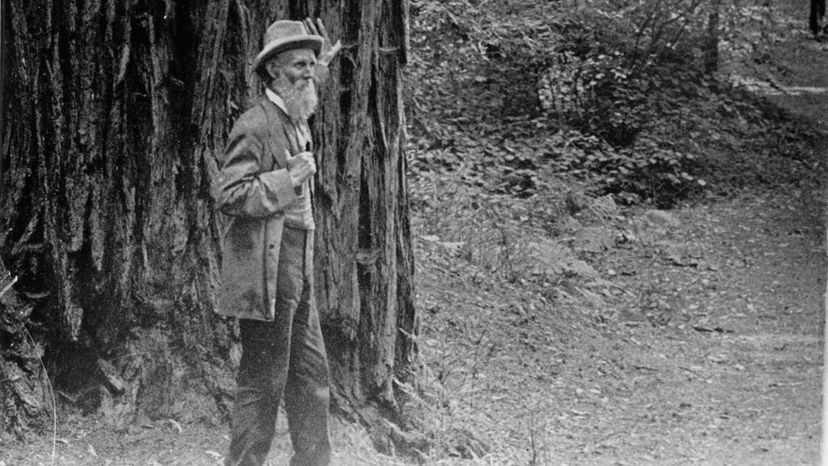

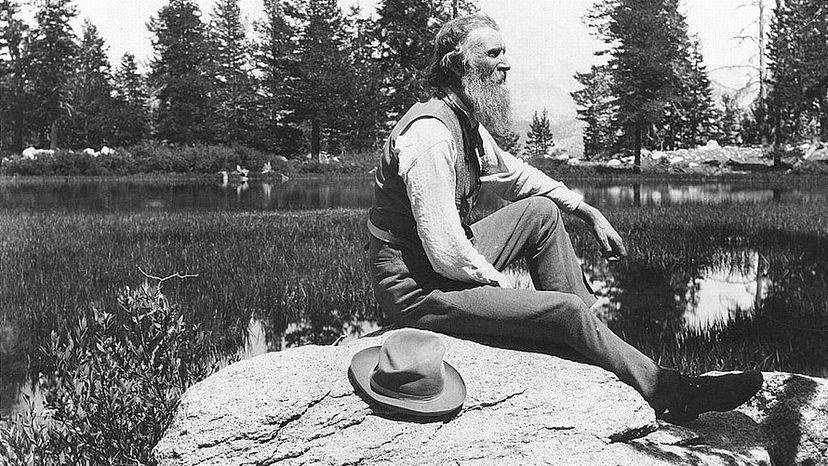

To conservationists, outdoor enthusiasts, and wildlife lovers, John Muir's name evokes countless connotations. Known as an explorer, farmer, inventor, writer, and more, the Scottish-born naturalist made a lasting impact on the landscape of the United States, and his legacy lives on in all corners of the country.

Born on April 21, 1838 in Dunbar, Scotland, Muir immigrated to the U.S. with his family at the age of 11, first settling in Fountain Lake, Wisconsin, and then relocating to Hickory Hill, a farm near the city of Portage, Wisconsin. Muir learned discipline at an early age: His father insisted that he and his younger brother work the family land each day, and as the young Muir explored the surrounding countryside, he developed an affinity for the natural world.

Advertisement

But Muir also had a taste for innovation, and as a young man, began inventing various tools and objects, including a device that literally tipped him out of bed before dawn. In his memoir, Muir described the "early rising machine" as "a timekeeper which would tell the day of the week and the day of the month, as well as strike like a common clock and point out the hours; also ... have an attachment whereby it could be connected with a bedstead to set me on my feet at any hour in the morning; also to start fires, light lamps, etc."

Muir first drew attention for his imaginative creations when he took his inventions to the state fair in Madison, in 1860. Later that year, he started his education at the University of Wisconsin, but left school three years later to travel — his goal was to explore the raw, untouched land of the northern states.

Muir sustained an injury in 1867 that changed the course of his life — while working at a carriage parts shop in Indianapolis, an awl pierced his right eye and he temporarily lost sight in both eyes. The fear of permanently losing his vision spurred Muir to shift gears, personally and professionally — he abandoned the industrial world and decided to further explore Earth's natural wonders instead. Some speculate that it was while he was recovering from his injury that he first heard about Yosemite.

Advertisement