Some of us admire the rise of women beauty entrepreneurs like Kim Kardashian, who's already made a reported $100 million with KKW Beauty, her cosmetics and fragrance brand. And you might be in awe of the way singer Rihanna leveraged herself to build her Fenty Beauty brand co-owned with LVMH. Products like her Pro Filt'r Soft Matte foundation — available in 50 shades — have made Rihanna the richest female musician in the world, with a fortune pegged at $600 million.

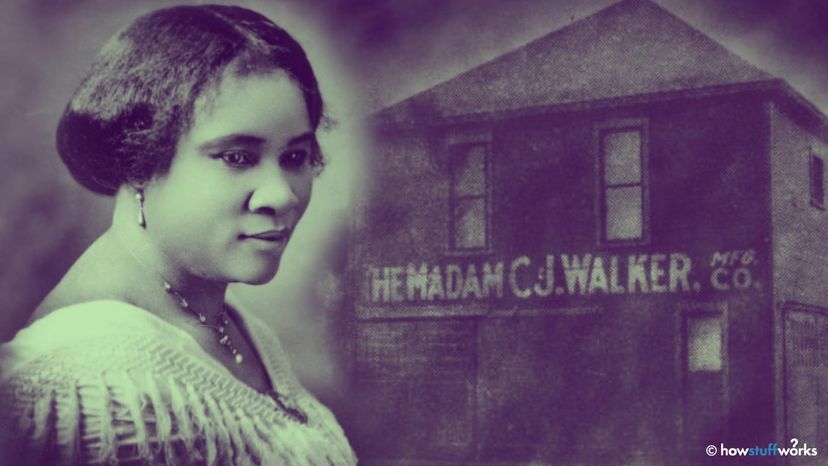

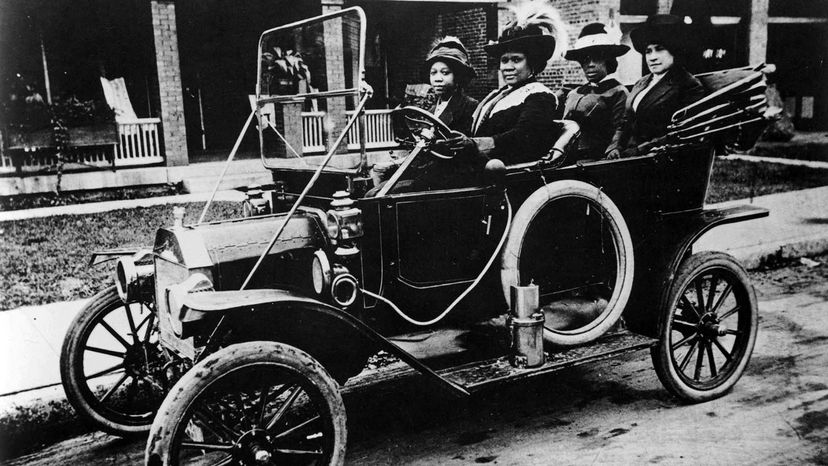

But both of these female entrepreneurs are following a trail blazed by Madam C.J. Walker a century ago. "Many consider her the first self-made American woman millionaire," says A'Lelia Bundles, Walker's great-great granddaughter and biographer. "For a woman in business and who launched her product before women had the right to vote, is pretty extraordinary."

Advertisement

Some reports claim Walker was the first Black woman to build a million-dollar fortune. But Guinness World Records lists Walker as the first self-made female millionaire, period.

And the fact that Walker was the daughter of sharecroppers, yet still built a national brand, empowered hundreds of women, and became a philanthropist and civil rights activist makes her story even more inspiring. The recent Netflix miniseries "Self Made," starring Octavia Spencer, is loosely based on Walker's life story.

Advertisement