Typhoid fever isn't a pretty disease. Painful diarrhea, high fever, lethargy, nasty red rashes, sleeplessness, headaches and coughing are typical symptoms of the illness. Left untreated, typhoid fever can result in death. Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella serotype Typhi, the parasite that spreads through water and food, making the disease highly contagious.

That was the case in turn-of-the-century New York City. Typhoid fever was a growing problem. The Department of Health had a lot on its plate; in addition to typhoid, it was trying to quell outbreaks of smallpox, tuberculosis, diphtheria and whooping cough that were also sweeping through the area. Luckily, scientists had developed a sophisticated understanding of microbial diseases and how they spread — even though most of the public didn't quite grasp all of it yet.

Advertisement

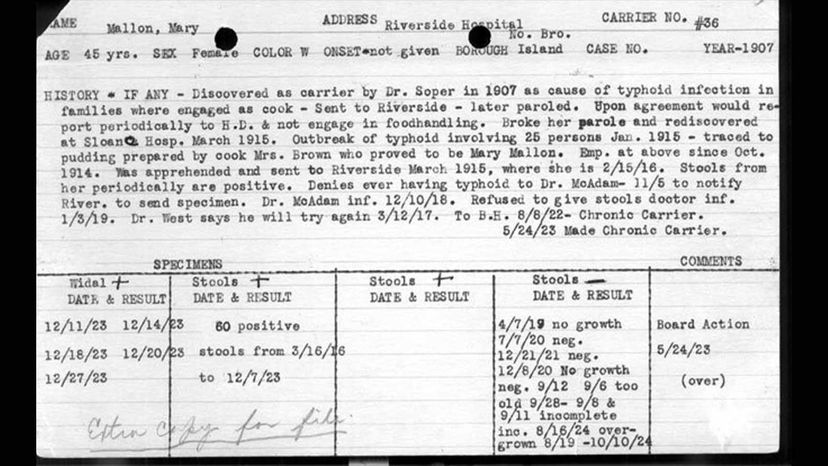

The Department of Health knew what caused typhoid, but dealing with the spread of the disease was another question altogether. It's something we are dealing with today in our attempt to quell the spread of coronavirus. We can't simply cast away those who are contagious to fend for themselves. So authorities must walk the line between keeping societies safe from debilitating illness and infringing on the personal rights of those who are sick. This same controversy reached a fever pitch in early 20th-century New York when it came to one individual: Mary Mallon, aka Typhoid Mary.

It might surprise you to learn that Mallon was actually immune to typhoid fever. Though it's uncommon, some people like Mallon are asymptomatic carriers. That means they can carry and spread the parasite but never have any symptoms. But even worse, Mallon was in a disastrous occupation for a carrier of typhoid fever: She was a cook.

Advertisement