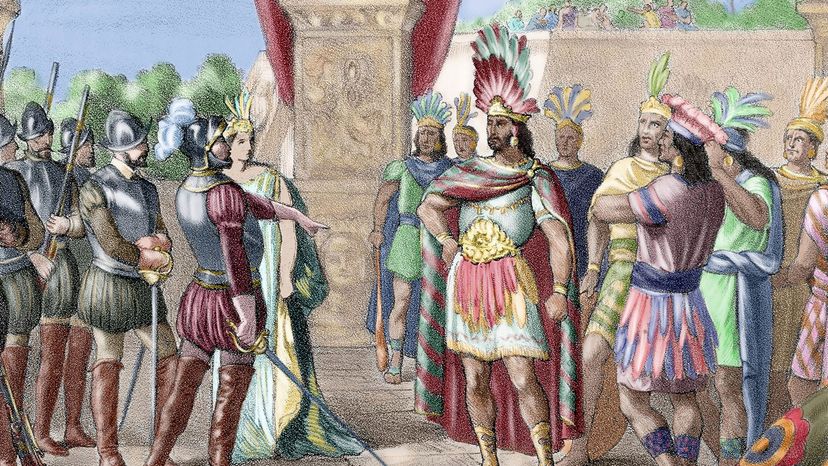

A little more than 500 years ago, a meeting occurred between two men that forever altered the course of history. The encounter took place in the magnificent Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, the seat of a wealthy and powerful Aztec empire that ruled over vast regions of central and southern Mexico. On Nov. 8, 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, after months of battling neighboring cities, entered Tenochtitlán and won an audience with the emperor we know as Montezuma II, the last fully independent ruler of the Aztec empire.

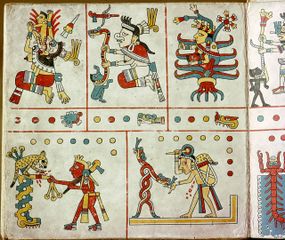

You probably think you know what happened next. Montezuma and his Aztec priests, believing the Spanish to be gods or the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy, basically rolled over and handed Tenochtitlán to Cortés. And that's how a Spanish invading force of just a few hundred men conquered an empire of millions and initiated centuries of Spanish colonial rule in the Americas.

Advertisement

But that story, and particularly that version of Montezuma, are inventions, says Matthew Restall, a historian of colonial Latin America at Penn State University and author, most recently, of "When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting that Changed History."

"There are two Montezumas: the Montezuma who actually lived — the real, historical Montezuma — and the Montezuma who was invented after his death," says Restall. "The invented Montezuma in many ways is the opposite of the real Montezuma. The invented Montezuma is weak and a coward and a failure. He's superstitious, afraid of the Spaniards and overwhelmed by them."

If that's not the real Montezuma, then what really happened on that fateful day in 1519? And who was responsible for reducing the mighty Montezuma into nothing more than a doormat for the Spanish conquest?

Advertisement