Key Takeaways

- New Englanders in late 18th and early 19th century believed in vampires, due in part to the tuberculosis epidemic.

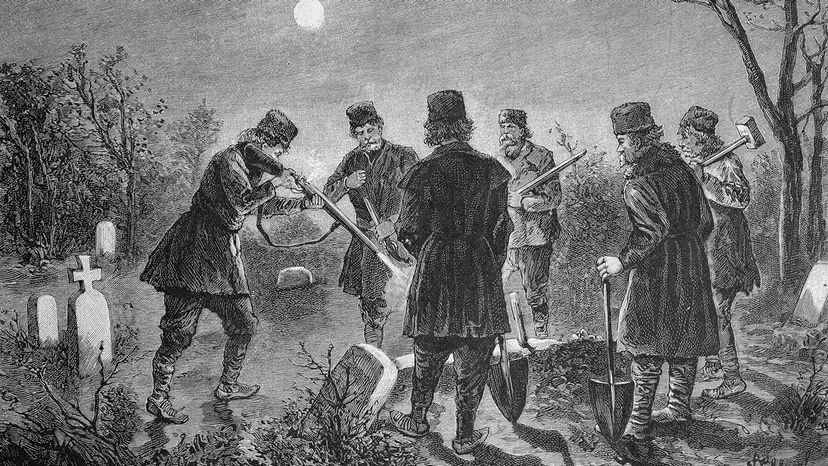

- Desperate villagers dismembered suspected vampires to stop the spread of disease.

- Rituals included burning organs and beheading corpses to prevent vampires from rising again.

It was a scene only Dracula and his blood-spattered ilk could love. In the late 18th and early 19th century, New Englanders were gripped by a vampire panic. In desperation, they began dismembering suspected vampires in hopes of driving off the terror and death that threatened to upend their lives.

But how did vampires come to invade the newly created United States?

Advertisement

It all began in some unfortunate New England villages, as tuberculosis (then called consumption) ravaged entire families and communities. This bacterial lung disease, which spreads easily among family members, has horrid symptoms, giving feverish sufferers an ashen appearance and sunken eyes. In some cases, blood would drop from their mouths.

It was a slow, wretched death – almost as if the life was gradually being drained out of them. It earned the name "consumption" for the way it caused dramatic weight loss. So severe was the epidemic that it claimed around 2 percent of the region's population from 1786 to 1800 and eventually killed perhaps 25 percent of the East Coast's citizens.

"Imagine a communicable disease a great deal slower to manifest than COVID-19, with symptoms even more ambiguous," says folklorist and author Michael Bell in an email interview. "One that did not explode through a population — leaving in its wake the dead and those who survived through good fortune or natural immunity — and then disappear or become latent. A disease that, instead, once it grasped a person, could go in and out of remission over a period of months, or years or even decades."

No one understood how diseases spread back then. All they knew was that as consumption victims perished, their surviving family members would begin to fall ill, one by one. Neighbors would be afflicted, too.

"Adding to its mystery, consumption seemed capricious in choosing its victims," says Bell. "Some families escaped intact while others were thoroughly decimated."

Advertisement