Americans are accustomed to thinking of the U.S. Constitution as the framework for the democratic system of government upon which the country was founded. But one of the reasons that the Constitution has worked for more than two centuries is that it's essentially a do-over. The Founding Fathers got to learn from and correct the mistakes made in the new nation's initial blueprint, a document called the Articles of Confederation, which was in force from 1781 until 1789.

"The main purpose of the 1787 Constitution was to overcome the Confederation's shortcomings," explains historian George William Van Cleve. He's a former research professor in law and history at Seattle University School of Law, where he wrote the 2017 book "We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution," and is currently an adjoint faculty member in history at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Advertisement

The Articles of Confederation resulted from wartime necessity. In June 1776, when the delegates to the Continental Congress authorized Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence, they realized that they had to replace British rule with some sort of national government. They also set up a committee to create a framework document. Given that Americans were trying to break free from the yoke of an oppressive royal regime, many weren't too keen on replacing it with a powerful central government.

"John Dickinson, a lawyer who was very conservative, was put in charge of the committee," explains historian Willard Sterne Randall, an emeritus professor at Champlain College in Burlington, Vermont, and author of numerous works on early American history, including "Unshackling America: How the War of 1812 Truly Ended the American Revolution."

Benjamin Franklin was also selected for the committee, and he took the opportunity to dust off the Albany Plan, a proposal for a colonial confederation under British rule that he had proposed back in 1754, according to Randall. One of Franklin's inspirations for that plan was the Great Law of Peace followed by the Iroquois nation.

While Franklin's Albany Plan hadn't gained much traction when he originally pitched it, this time – perhaps because the Continental Congress was in a hurry – he had more luck. "The Articles of Confederation closely followed the Albany Plan, in all its defects," Randall says. Take out the allegiance to the British crown, and "there were basically no differences."

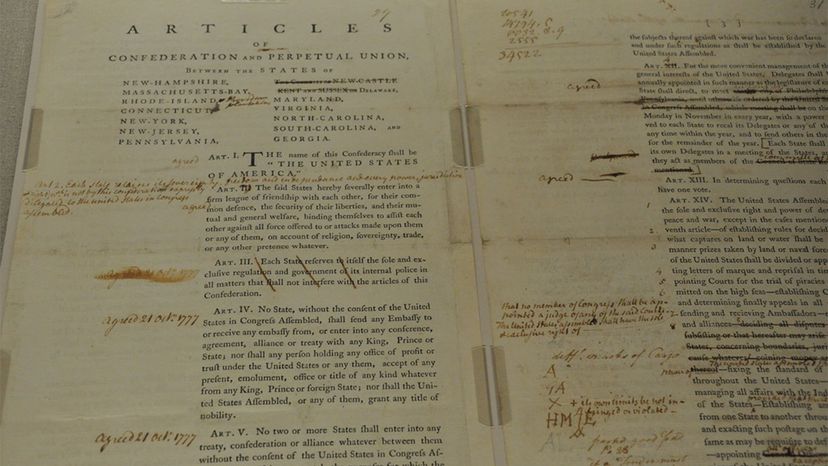

The text of the Articles of Confederation envisioned the U.S. as a loose group of sovereign states that, to quote from the Articles, entered into "a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare."

Advertisement