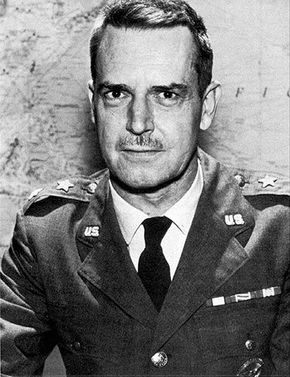

But Lansdale was clearly proud of his most brazen and bloody psychological warfare operation in the Philippines. According to Lansdale, a Huk squadron had set up camp on a hill outside of a village. The village leaders claimed that the Huks threatened to kill any village "bigwigs" who didn't cooperate.

Lansdale sent in a CIA-trained "combat psywar squad" with clear instructions. First, the Philippine psyops agents were to plant stories among the villagers that an aswang was haunting the hill where the Huks were camped. Then after a few days — enough time for the rumors to infiltrate the Huk encampment — it was time to strike.

Here's how Lansdale described the operation in his own words:

"[T]he psywar squad set up an ambush along the trail used by the Huks. When a Huk patrol came along the trail, the ambushers silently snatched the last man of the patrol, their move unseen in the dark night. They punctured his neck with two holes, vampire-fashion, held the body up by the heels, drained it of blood, and put the corpse back on the trail. When the Huks returned to look for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member of the patrol believed that the asuang had got him and that one of them would be next if they remained on that hill. When daylight came, the whole Huk squadron moved out of the vicinity."

To be clear, a CIA-trained squad of Philippine soldiers kidnapped Huk fighters and killed them vampire-style, leaving their bloodless corpses behind. Clark of The Aswang Project thinks that's pretty messed-up.

"To me, this is a brutal and horrific scene with or without the aswang lore," says Clark. "It's not even clear if the Huks believed it was an aswang killing the people or if they were horrified at the desecration of the deceased by the CIA-advised troops."

In his research, Clark found that people in that region of the Philippines believed in a creature called the manananggal, a self-segmenting type of aswang that fed on the fetuses of pregnant women, not a Dracula-style blood-sucker.

"There was no 'vampire-like' aswang lore in the region, so I am skeptical that this psywar tactic even worked," says Clark, "other than the terrifying visual of seeing your friend strung up like that."

Clark also points out that the "aswang scare tactic" was apparently only used once to dislodge a Huk squadron of between 100 and 300 soldiers. It didn't win the entire war. In the end, though, the Huk insurgency was worn down by years of fighting the U.S.-backed regime. Luis Taroc, the Huk leader, surrendered in 1954.