From the 1600s through the 19th century, West Africa was home to a succession of sophisticated and powerful kingdoms. As in Europe, Asia and the Americas during this time, rival powers in West Africa waged bloody wars for economic, political and cultural dominance.

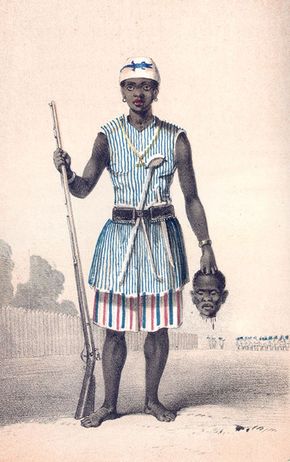

For centuries, the Kingdom of Dahomey was the wealthiest and most feared of these West African powers, and Dahomey became famous for its elite army of women warriors called the Agojie, whom wide-eyed European observers dubbed the "Dahomey Amazons" after their fictional counterparts in Greek myth.

Advertisement

The hit 2022 film "The Woman King" stars Oscar-winner Viola Davis as Nanisca, an Agojie general bravely defending her kingdom, led by King Ghezo, against an unholy alliance between Dahomey's archrival, the Oyo Kingdom and European slave traders.

But while the real-life Agojie, the world's only all-female army, were immensely brave and skilled warriors, the film has been criticized for misrepresenting Dahomey and King Ghezo's true role in the Atlantic slave trade. The truth is that from 1640 to 1860, much of Dahomey's wealth came from raiding rival kingdoms and selling millions of captives to Portuguese slave traders. And as Dahomey's finest and fiercest warriors, the Agojie were critical to the success of those slave-capturing raids.

After the slave trade ended in the mid-19th century, Dahomey's storyline changed and the Agojie were indeed able play the role of freedom fighters, as the filmmakers would like us to see them. The enemies at that time were French colonizers who wanted to seize control of West Africa. As always, the Agojie fought valiantly for their king, but their story didn't have a happy ending.

Advertisement