For years after World War II, in most of what was considered the "civilized" world, the truth behind Japanese Imperial Army Unit 731 was quietly swept away. Facts were suppressed. Memories questioned. Reports denied.

Even today, the true extent of Unit 731's wartime actions — horrendous, deadly medical experiments and lethal biological weapons testing on unsuspecting Chinese civilians — is known largely only to historians and scholars.

Advertisement

But the facts are out there for those who seek them. And for those who seek to use them for their own personal reasons.

"I think that it has become a piece of this tortured dialogue over the war between Japan and China. The Chinese have seized upon this quite a bit. And the Japanese right, the nationalist right, their basic view is that, 'Oh, the Chinese. This is all political.' ... And there is a certain truth to that," says Daniel Sneider, a lecturer in international policy at Stanford's Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. "There is a 'uses of the past' question here. Perhaps you could say it's cynical in that everybody does it."

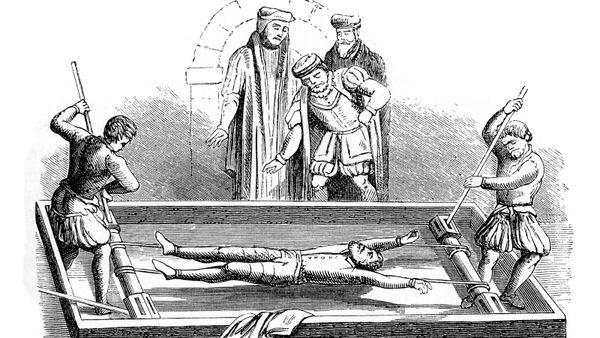

The truth is that Japan's Unit 731 committed some of the most heinous war crimes ever. Thousands of prisoners were killed in cruel human experiments at Unit 731, which was based near the northeastern China city of Harbin, north of the Korean peninsula and on a border with Russia. Perhaps hundreds of thousands more — maybe as many as a half-million — were killed when the Japanese tested their biological weapons on Chinese civilians.

The exact number of dead is not known. It may never be known.

"It's very difficult to calculate," says Yue-Him Tam, a history professor at Minnesota's Macalester College and co-author of a book entitled, "Unit 731: Laboratory of the Devil, Auschwitz of the East (Japanese Biological Warfare in China 1933-1945)." Tam, born and raised in China, has taught a class at Macalester on war crimes and memory in contemporary East Asia for more than 20 years. "If you include those victims who suffered from the other activities — not necessarily just used as human guinea pigs — the bombs in China ... it's very difficult to calculate."

Advertisement