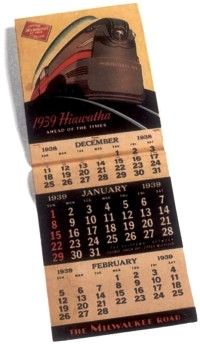

The period between 1930 and 1945 was a time of contrast and change. The railroad industry, shrunken by economic crisis and competition from the automobile, developed new ways, to lower costs and attract passengers. Meanwhile, diesel locomotives began to replace steam engines as the nation prepared for war. Literally everything moved by rail during the conflict, leaving the railroads exalted but exhausted as they approached the postwar era.

The railroad industry entered the 1930s in a state of deep pessimism. While most business and government leaders proclaimed that the national economy was in good condition, unemployment had risen from 1.5 million in late 1929 to an estimated 4 million by the spring of 1930.

Advertisement

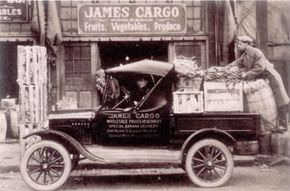

Railroads had not come through the 1920s in very good condition. Nationalization during World War I left the major railroads worn out, and reinvestment was hampered in the capital markets, which favored more lucrative -- and speculative -- outlets for investment. Railroads also suffered the effects of restrictive governmental regulation, public investment in competing transportation systems, and the loss of passenger business to the automobile. The national economic collapse that began in 1929 only sharpened the predicament faced by railroads since 1920.

Unemployment had risen to nearly 5 million by January of 1931. The Depression reached a low point in mid-1932, with unemployment standing at 12 million, the overall economy having contracted by 40 percent, and industry producing at half of 1929 levels. Railroad employment fell by 42 percent during the same period. Employees who weren't furloughed had to bump fellow workers with lower seniority or accept demotion in order to keep working. Increased freight tariffs were granted in 1931 to shore-up falling revenues. This proved to be a disaster, as shippers diverted traffic to lower-cost trucks. In January of 1932, railroad management and labor agreed to a 10 percent reduction in wages for one year. The net income of railroads plummeted from $977 million in 1929 to a loss of $122 million in 1932; the industry would not be profitable again until 1937.

Capital investments were cut, and maintenance was deferred to the greatest extent possible. Locomotive sales plummeted during the early 1930s, and most railroads had long "dead lines" of locomotives collecting dust in storage yards.

Unused engines and cars tied up substantial amounts of capital, had costs associated with bond interest, and weren't earning any money to pay these costs. One third of the nation's railroads went into bankruptcy during this period, and the cruel realities of railroad economics spelled the demise of many companies in the 1930s.

The "New Deal" of President Franklin Roosevelt sought to stabilize the economy in a number of ways. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation had been chartered during the Hoover administration to loan money to essential businesses, including banks and railroads, but had accomplished little before 1934. Despite Roosevelt's skepticism about the economic benefit of federal public works spending, his new Public Works Administration funded schools, courthouses, hospitals, highways, bridges and other transportation improvements. Though thousands of miles of highways were built, the largest railroad project of the era was the RFC/PWA-financed electrification of the Pennsylvania Railroad between New York City and Washington, D.C.

Advertisement