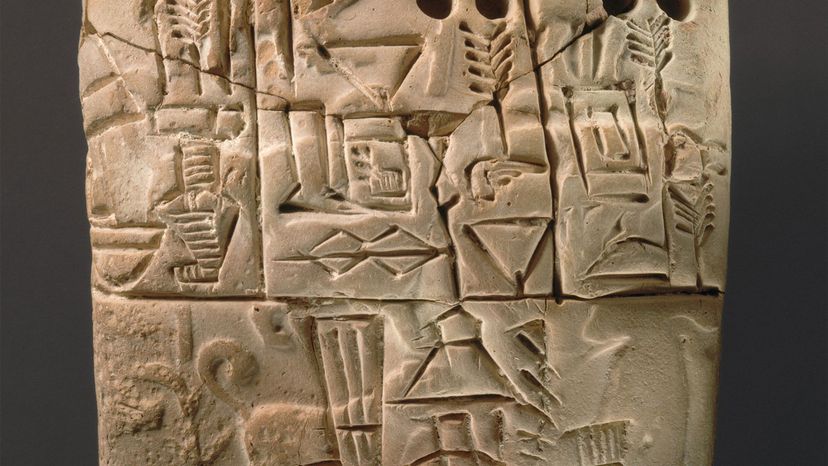

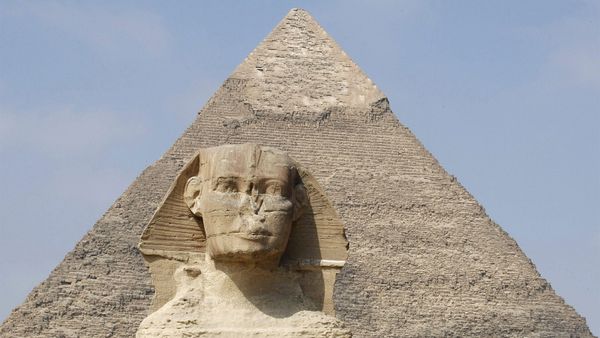

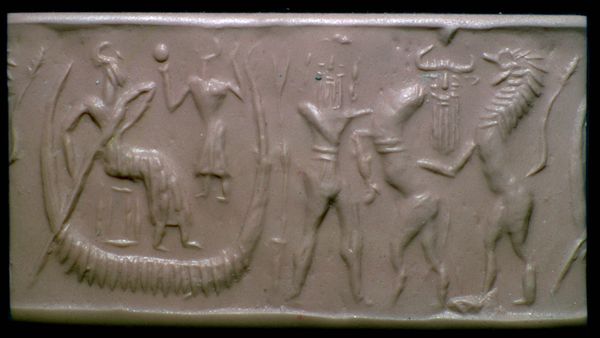

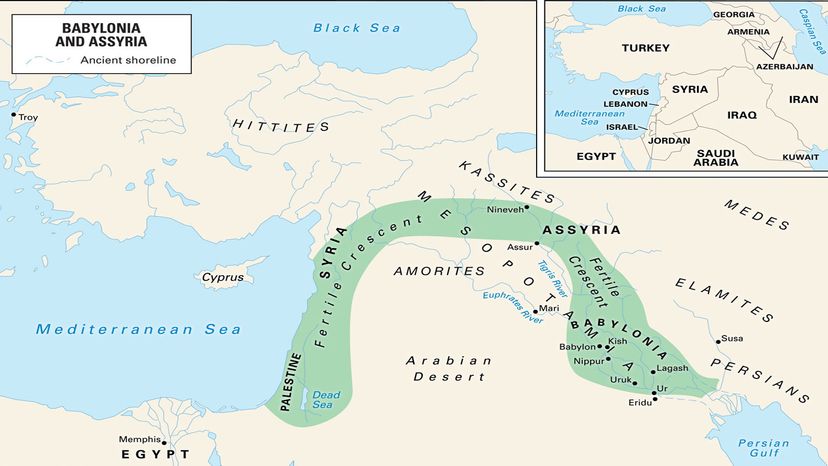

When the last ice age ended nearly 12,000 years ago, the climate warmed, the seas rose and rains fell on the grassy steppes of the ancient Near East. It was here, archaeologists believe, in a semicircular region now known as the Fertile Crescent, that agriculture may have first taken hold, some of the world's first great cities were built, and humans developed some of the first clear hallmarks of "civilization," including writing, mathematics and religion.

The term "Fertile Crescent" was coined in 1914 by the American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted in his popular high-school textbook "Outlines in Human History." He used it to describe a roughly crescent-shaped region encompassing modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and parts of Turkey and Iran.

Advertisement

"The earliest home of men in this great arena of western Asia is a borderland between desert and mountain — a kind of cultivable fringe of the desert — a fertile crescent having the mountains on one side and the desert on the other," wrote Breasted. "This great semicircle, for lack of a name, may be called the fertile crescent."

More than 10,000 years ago, the nomadic peoples of this region harvested the wild grasses that grew in the rain-fed foothills and gathered together in small village settlements. Over millennia, they began to domesticate wheat and barley (beer was one of their first and best ideas), and to breed wild game into domesticated goats and sheep for meat, dairy and wool.

The agricultural revolution began in earnest when farmers learned how to irrigate the fertile soils of the river valleys, where mineral-rich layers of silt enabled larger and more consistent harvests, which supported larger and more permanent human settlements.

Advertisement