Eleven thousand years ago, the world looked different.

Not only did lush forests exist where there are now deserts, grasslands where there are now coral reefs, humans hadn't yet begun building many things. Of course, we can't ever really know exactly what our ancestors were up to tens of thousands of years ago, but one place — the archaeological site Göbekli Tepe — can give us a few clues.

Advertisement

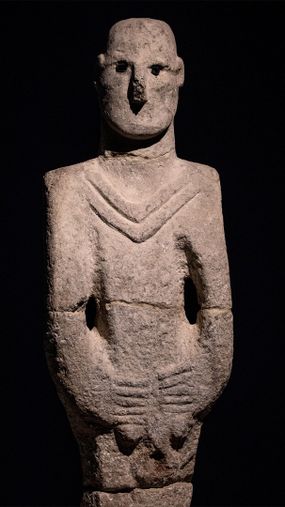

Göbekli Tepe, a monument along the lines of Stonehenge situated in the Germuş mountain range of southeastern Turkey, was discovered by a team of American and Turkish surveyors in the 1960s, but their discovery of limestone slabs and flint artifacts wasn't recognized for what it was until 1994, when a German archaeologist named Klaus Schmidt stepped in and realized its significance. It is a mysterious site to this day, partly because we can make so few assumptions about the people who built it.

"Monuments, generally speaking, are a particular example of architecture standing out due to their size and/or the effort necessary to create them," says Jens Notroff, an archaeologist who has worked on the Göbekli Tepe Project since 2006, in an email. "Göbekli Tepe is a noteworthy example in this context since the monuments there mark the first yet known example of monumental architecture, and that they were constructed in a cultural context of still highly mobile hunter-gatherers."

A Mobile Hunter-gatherer Society

From what archaeologists have been able to surmise from the Göbekli Tepe site itself, the people who built it were highly mobile hunter-gatherers — there's no evidence that they kept livestock, planted their own food or made metal tools. This jives with what we know of the people in the early Neolithic:

"Göbekli Tepe is from a period called 'Pre-Pottery Neolithic,' which means before the invention of ceramic vessels," says Notroff. "We know settlement sites and their architecture from the period and region which were inhabited for a longer time. Apparently, the buildings unearthed at Göbekli Tepe do not really resemble this 'typical' settlement architecture, but rather a peculiar type of building interpreted as 'special purpose' communal buildings."

Advertisement