During the Dark and Medieval Ages, the Catholic Church countered scientific inquiry with painful death. With the dawn of the Age of Exploration, rational thought began to emerge from the shadows. The world opened up along oversea trade routes, and merchants returned to Europe from strange and eldritch lands with impressive relics. These were prized by early scientists, who collected the items, forming the first wunderkammern.

Looking in on these wunderkammern was fashionable among Europe's wealthy classes. But to those who amassed the items, wunderkammern were far more than passing fancies. Each item in these collections presented an opportunity to explore and catalog one more piece of the world.

Some artifacts were more dubious than others. One may have found a mummy's hand situated next to a reputed mermaid's hand. And their arrangement within the cabinet or room followed no aesthetic pattern. Instead, the items were tucked away wherever each fit. As a result, macabre juxtapositions often emerged, like a perfectly symmetrical dried starfish book-ended by a syphilis-ravaged skull and a fetish (an idol representing a god) from some equatorial cult.

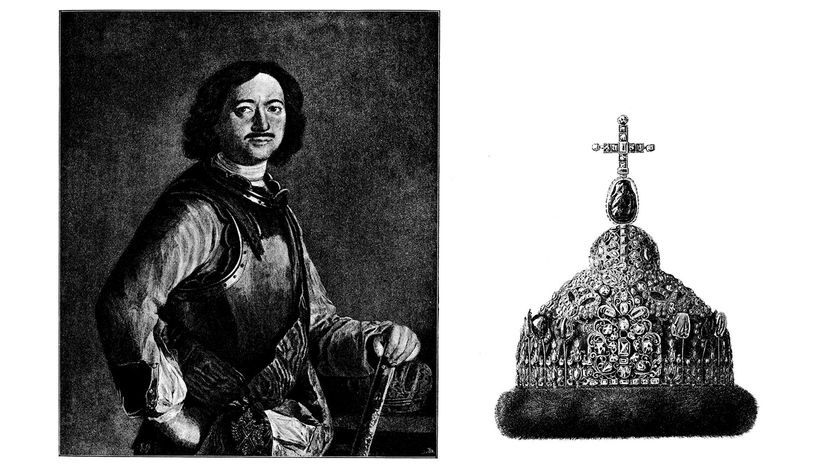

Other collections were of a medical nature; anatomical oddities like conjoined twins were highly prized, as were abnormalities like human skulls with horns. Some collections were thematic, with many types of a similar artifact that were used as bases for comparison. Peter the Great's cabinet of curiosity featured scores of teeth he'd personally pulled -- he considered himself a dentist [source: Slate].

Wunderkammern were in vogue in Europe and provided Peter with a perfect opportunity to slake his natural thirst for knowledge while introducing an occidental appeal to his nation. Peter was interested in bringing Russia out of cultural isolation and into a more Eurocentric society. A government under constant threat of usurpation kept him busy, and he had to purchase others' collections rather than collect his own novelties. He had a standing order for his merchants and military to bring back any items of interest for his wunderkammer.

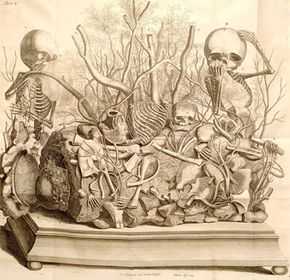

He invested in two collections that had achieved considerable prominence. One was that of Dutch scientist Frederik Ruysch. His wunderkammer was a spectacle, indeed. It was as much a statement on life and death as it was about the demystification of anatomy. Ruysch developed techniques for preserving tissue, and he used his methods to create amazing works of art. He often featured fetal skeletons in woodland scenes. Closer inspection reveals the trees and other flora -- the "woodland landscape" -- to be intricate constructions of veins and arteries. The handkerchiefs into which some skeletons wept over the folly of life were flayed brain tissue [source: Gould].

Peter also purchased the collection of another Dutchman, Albertus Seba. He sold the contents of his wunderkammer to Peter in 1717 for 15,000 guilders [source: Towbridge Gallery]. Seba's contribution to Peter's collection consisted largely of exotic animal specimens, for which the Dutchman traded medicine to sailors. Preserved items like squid, poisonous toads and butterflies were shipped from Amsterdam to St. Petersburg.

Although these exhibits sound morbid and strange, there was a purpose behind them. To Peter, the study of abnormal specimens meant dispelling popular myths about the involvement of the devil in the development of what the peasantry considered to be "monsters" [source: Kunstkamera]. As a result, a major part of Peter's collection consisted of pickled fetuses and sections of the human body. This part of the wunderkammer extended to the animal kingdom, as well. It included a two-headed sheep and a four-legged rooster [source: British Library].

The contributions to human understanding that Peter's and others' collections of oddities generated is incalculable. But wunderkammern also left behind other traces over the centuries. Find out about the legacy of wunderkammern on the next page.