The American Civil War is the bloodiest conflict in which the United States has ever engaged. More than 600,000 American soldiers lost their lives in four years [source: Library of Congress] at a time when the total U.S. population was around 34,000,000 [source: U.S. Census]. This is proportional to about 5.2 million Americans dying in a four-year period beginning in 2008.

No one -- no matter how prestigious -- was exempt from the divisiveness of the Civil War. While she and her husband represented the Union's interests, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln had six close relatives who fought for the Confederacy. Three died in battle [source: NNDB]. And the leader of the Confederate Army, Gen. Robert E. Lee, resigned from his 30-year post in the U.S. Army to fight for the Confederacy. Perhaps no family was more affected by the divide between North and South than the Crittenden family, though.

Advertisement

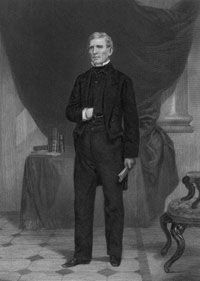

John J. Crittenden was a senator from Kentucky, the state maybe most divided by the Civil War. Sen. Crittenden struggled to hold his state together as dissident factions debated over whether to side with the Union or Confederacy. Originally, Kentucky had been neutral. But after contingents from both the Union and Confederacy traveled to Kentucky (Confederate troops entered first), the state government became divided. Crittenden was torn by the disputes between the Union and the Confederacy. While he ultimately remained loyal to the United States, he also proposed a plan (the Crittenden Compromise) which called for the federal government to leave the issue of slavery to the states [source: Murfreesboro Post]. His plan ultimately failed.

Kentucky's ambivalence was reflected in the Crittenden family as well. The senator's sons, George Bibb Crittenden and Thomas Leonidas Crittenden, both served as generals in the Civil War. However, each fought for a different side. While George, the eldest, served the Confederacy, Thomas commanded Union troops.

Read about the Crittenden brothers on the next page.

Advertisement