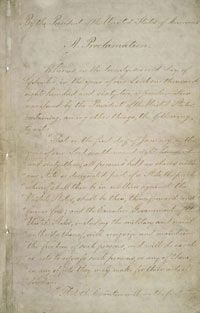

Here's a question for your next trivia game: How many slaves did the Emancipation Proclamation free?

Answer: zero.

Advertisement

But you learned in school that President Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation, right? Well, the history books may have been stretching the truth.

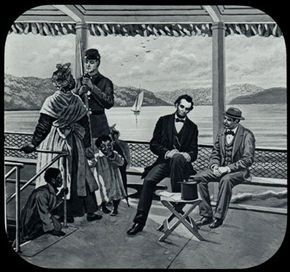

An important fact to know about Lincoln is that he was a savvy politician. The Emancipation Proclamation was a document that officially changed nothing -- Congress had already passed laws outlawing slavery in the rebel states, which was the only territory Lincoln covered in the Proclamation. (Lincoln the politician wanted to keep border-state voters happy.)

And the Proclamation took effect on Jan. 1, 1863, two years after the Civil War began -- what took Lincoln so long? Again, politics. He couldn't very well have issued a decree freeing the slaves when the North was losing the war. There would be no way to enforce the Proclamation, thus making it appear a desperate and hollow threat. So Lincoln waited until a big Union win, at Antietam.

Speaking of enforcement, the Proclamation technically freed slaves in another country -- the Confederacy had seceded. So what happened to the slaves in the Union? They had to wait until 1865 for the passage of the slavery-abolishing 13th Amendment, which wasn't officially ratified until after Lincoln was assassinated.

But the Emancipation Proclamation must have done something. Otherwise, why would we consider it such an important document?

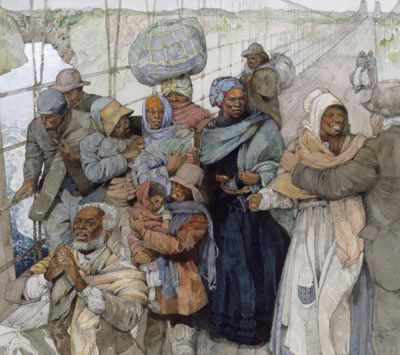

While it didn't technically set anyone free, the Proclamation was part of Lincoln's strategy to demoralize the South, and it worked. Poorer Southern whites resented that they were now fighting a war to protect wealthy plantation owners who were desperate to hold onto their "property." And as word of the Proclamation spread, slaves left those plantations en masse. Their exodus even helped turn the tide in the siege of Vicksburg, a vital Union win.

Additionally, France and England, which had been secretly helping the South, could not officially recognize a country that still enslaved other human beings. Europe also could not provoke a country that, according to the Emancipation Proclamation, was now fighting slavery.

And if all that weren't enough, the Emancipation Proclamation can be credited with giving this country another state.

Beyond politics, the Emancipation Proclamation became a symbol of what the Civil War was heading toward. It was no longer about states' rights, rebellion and nullification -- with one document, Lincoln turned it into a war to end slavery.

Advertisement