On January 27, 1944, the besieged Soviet Union city of Leningrad, where an estimated one million people had died from starvation, disease, and constant shelling, was finally fully freed from encirclement after almost 900 days. This was just one of the small victories that led to the D-Day invasion and the end of World War II.

It was the end of a terrible epic of suffering in which the old had been sacrificed to save the young on the principle of Soviet Union doctrine that "he who does not work does not eat." Life in wartime Leningrad represented the idea of "total war" at its most intense. Every citizen was a potential victim. Everyone was obliged to do their utmost to defend the city. "We are all on death row," confided a nurse to her diary, "we just don't know who is next."

Advertisement

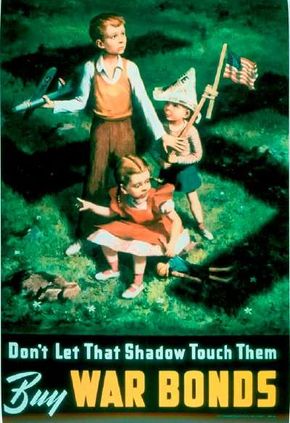

The year 1944 saw every combatant nation exert itself to the fullest extent. After three to four years of warfare, populations had become used to ceaseless rationing, travel restrictions, air-defense blackouts, and long hours in fields and factories. In Europe, approximately two-thirds of the countries' national product was diverted to war. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union between them mobilized about 46 million men and women in the armed forces. These were levels of effort that few populations could sustain for long.

World War II Image Gallery

Total war necessitated the mass participation of women, who comprised 35 percent of the British and American workforce and more than 50 percent in Nazi Germany and the USSR. Only in the United States, whose geographical immunity freed the population from the more onerous restrictions, did the war produce an economic boom. The American economy alone could afford large armaments while maintaining reasonable living standards.

For the first six months of 1944, the pace of advance on land against the Axis slowed. Both sides knew that at some point Europe would be invaded from the west, and that this blow, if successful, would probably ensure the defeat of Nazi Germany and its European allies. But while preparations went ahead for the invasion of France, Allied forces engaged in prolonged and bitter fighting on other fronts.

In Italy, the German redoubt around the ancient monastery of Monte Cassino, perched high in the mountains, proved a firm barrier. On January 22, an Allied task force landed at Anzio, farther up the coast toward Rome, in the hope of outflanking the German line. But the beachhead was contained, and for five more months the front stalled. Only on May 18 did a fierce assault by a Polish unit fighting with the Allies secure Monte Cassino. This victory broke the German line. On June 4, American forces entered Rome. The German army retreated northward to a new defensive position, the Gothic Line, from Pisa to Rimini.

In the Soviet Union, the momentum achieved after the Battle of Kursk (summer 1943) slowed. But in the winter of 1943-44, the Soviets advanced into the Ukraine against isolated counteroffensives from the German army. After six months, Soviet Union forces reached the Romanian and Hungarian borders. The Crimea was cleared, and on May 9 the Germans surrendered Sevastopol. Farther north, the Red Army reached the edge of the Baltic States and was poised for an assault on Poland.

In the central Pacific, the Americans' island-hopping campaign brought them control of the Gilbert Islands and Marshall Islands by February 1944. Moreover, landings along the coast of northern New Guinea isolated Japanese strongholds and brought the Philippines within striking distance. The Japanese carrier base at Truk in the Caroline Islands was neutralized by superior American airpower, and the advance on the Mariana Islands in June destroyed Japanese land-based airpower there.

When U.S. Marines landed on the Mariana island of Saipan on June 15, the Japanese fleet finally intervened. Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo led nine carriers and 450 aircraft against 15 American carriers and more than 900 aircraft. The Battle of the Philippine Sea was fought from June 19 to 20. By the end of it, the Japanese had lost the majority of their aircraft and withdrew. The 30,000-strong Japanese garrison on Saipan fought to the death, and by early July the island was in American hands. From the Marianas, it was possible to begin long-distance bombing of the Japanese homeland with the new B-29 Superfortress.

Throughout these months, the Allies' western strategy was dominated by preparation for Operation Overlord, the invasion of northwestern France by a combined American and British Commonwealth force. The planning and administration alone absorbed 300,000 people. A combined arms assault on a heavily defended coastline was an operation fraught with risk. The deadlock at Anzio and the cost of assaults in the Pacific against small but determined garrisons made it clear that a frontal attack on continental Europe across the Atlantic Wall defenses would be a costly and uncertain enterprise.

The attackers did have some clear advantages. Britain and the United States had overwhelming naval power, and after their victory in the Atlantic in 1943, they could maintain seaborne logistics without considerable difficulty. The Allies also had attained air superiority over Western Europe in February and March 1943. During the invasion, 12,000 aircraft would support Allied forces against only 170 serviceable German aircraft. The Allies also could choose the place and time of the invasion, as long as it could be concealed from the enemy.

The greatest success enjoyed by the Allies in the run-up to Overlord was in the field of disinformation. The extensive use of double agents, careful camouflage, and the strictest secrecy prevented the Germans from guessing the invasion point or the precise day. The German commander of the Atlantic Wall, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, believed like most of the high command that the Allies would take the short route across the English Channel toward the Pas de Calais. Limited German forces were kept in Normandy, France, but it was always assumed that an attack there would be a feint.

U.S. general Dwight D. Eisenhower would decide the final date. He had been appointed the supreme commander of Allied forces due to his great skills as an organizer and diplomat, qualities he needed to the full in holding together his command team. General Marshall thus could be held in reserve in case the invasion failed and a second one had to be mounted. The Allies had appointed General Bernard Montgomery, who had already defeated Rommel once, as their ground forces commander.

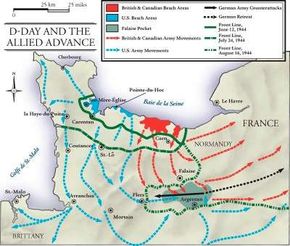

In late May, the final battle plan was approved. Allied forces would attack in Normandy across five selected beaches. Once established, the bridgehead would be consolidated and then used as the launchpad for a breakout. The Allies would roll up the German front in France and push it back to the Rhine River.

The date for the invasion was fixed as early May, but postponed to June when more landing craft would be available. The weather in early June was so severe that German commanders relaxed. Rommel went back to Nazi Germany for his wife's birthday. Eisenhower set D-Day -- military shorthand for the first day of any major operation -- for June 5. But with no improvement in the weather by June 4, Eisenhower was faced with a difficult choice. At 9:45 p.m. on the 4th, he gathered his commanders to order the invasion for June 6. Though heavy rain continued outside, there was better meteorological news. Eisenhower said quietly, "OK, let's go," launching the largest seaborne invasion in history.

Twenty-seven hundred ships moved to position, and in the early hours of June 6 they approached the French coast. By the time German forces were alerted, the invasion was upon them. A colossal naval barrage and around-the-clock bombing reduced resistance on all but one beach, Omaha. There, U.S. forces faced stiff opposition from defenders who were dug in on high cliffs and had by chance avoided the worst of the bombardment. The American army did not have a foothold on Omaha until the evening. On the other beaches, rapid progress was made and a bridgehead a few miles wide and deep was carved out in the first hours. Within days, more than 300,000 soldiers and 54,000 vehicles went ashore, using prefabricated harbors known as "Mulberries" that had been towed in sections across the Channel.

Throughout June, the Allies made slow progress. U.S. forces cleared the Cotentin Peninsula further west, but the city of Caen -- which was to be the hinge of the whole operation -- remained in German hands. Relations between Eisenhower and Montgomery worsened. Historians to this day have argued that the British were too cautious in the face of fierce German resistance. Britain's chief concern was to avoid defeat at all costs. Most of the Anglo-American troops lacked battle experience, and the invasion was a steep learning curve. At no point in June could ultimate victory be taken for granted.

On July 1, Rommel began an assault on the British line with five panzer divisions, provoking the fiercest fighting of the campaign so far. American attempts to accelerate the breakout southward (code-named Operation Cobra) were slowed by the rapid redeployment of German armor.

The situation was made more awkward for the Western Allies by the rapid success of the Red Army in the East. Stalin had promised a renewed summer campaign to coincide with Overlord. The operation, code-named Bagration, was undertaken against the largest concentration of German forces in the East, Army Group Center. Bagration also was meticulously prepared, veiled in secrecy, and covered by a deception operation as successful as that in the West. Soviet Union forces moved into concealed positions, while partisan attacks disabled German communications and Soviet Union aircraft pounded German positions.

On June 22, the full-scale operation was launched with devastating success. Within a week, Soviet Union forces broke through the German defensive line, captured tens of thousands of German soldiers, and advanced at a rate of up to 25 miles per day. Farther south, the Ukrainian campaign began again with assaults toward Lvov. Here, too, German defense crumbled. While the Western Allies were facing 15 German divisions, the Red Army engaged 228 German divisions across a 500-mile front.

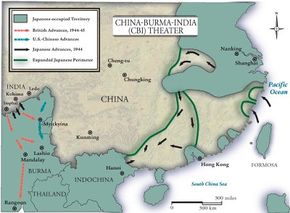

Farther east, Japan launched a wide offensive across large tracts of central China. This was one of the last major offensives by the Axis powers, and it came at a time when Japanese fortunes in the central Pacific were waning. On April 18, the Japanese army began Operation Ichi-Go to destroy air bases that could be used by American aircraft to attack the Japanese mainland. The operation was also designed to open a continuous overland route (road and rail) between Manchuria and Singapore to facilitate the importation of strategic resources from Japanese conquests in the Southeast without interdiction from American submarines and aircraft.

On May 27, the Japanese launched a separate operation to capture the area of the middle Yangtze River. After six months of fighting, Japanese-held territory was consolidated into a single bloc. The campaign caused a growing rift between Chiang Kai-shek and the Americans, represented in China by General Joseph Stilwell. With the loss of air bases, there was little more that the Americans could achieve. Stilwell was recalled at Chiang's insistence, and the Chinese theater remained a contest between Nationalist, Communist, and Japanese forces over the future of Eastern Asia.

In the next section, get a detailed timeline of daily World War II events from January 1-10, 1944.

For more timelines and information on World War II events, see:

- World War II Timeline

- The Battle of the Bulge: July 1944-January 1945

- Italy Falls to the Allies: February 1943-December 1943

Advertisement